Zhenwu AI chip and Alibaba's three-pillar AI stack — chips, cloud, and models

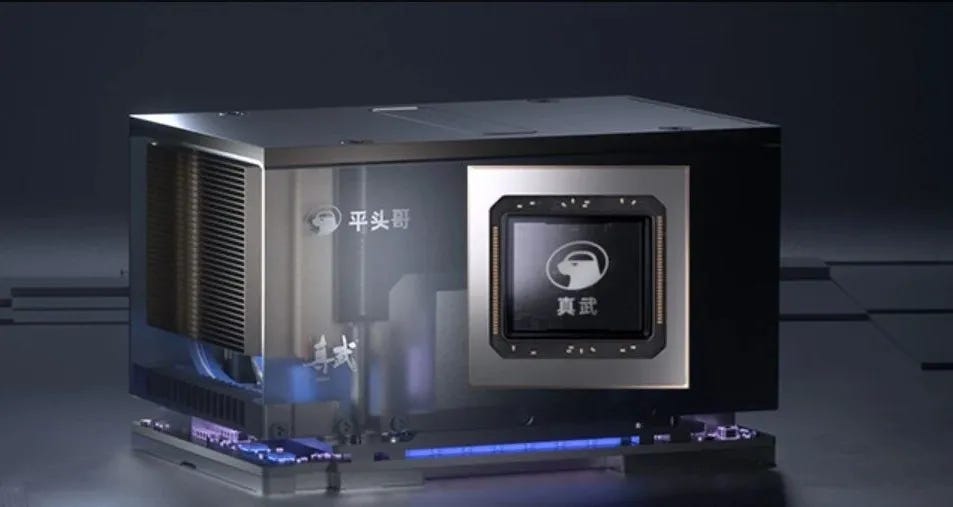

Today is a genuinely meaningful day for China’s AI industry — and arguably for China’s semiconductor industry as a whole. Alibaba’s chip arm, T-Head, has officially unveiled a high-end AI chip called Zhenwu 810E (真武810E)on its website. Below is an analysis:

To be clear, this didn’t come out of nowhere. For years, there have been persistent rumors in the Chinese tech community about T-Head developing its own PPU (a proprietary parallel processing unit). At one point, fragments of technical details even made it onto China’s evening news, which triggered intense discussion among chip insiders. Still, until today, everything about this PPU remained vague and incomplete. Now, “Zhenwu” has finally stepped fully into the public eye.

What really matters, though, is that this is Zhenwu’s first public appearance — not its first real deployment. Long before today’s announcement, the chip had already been running at scale inside Alibaba Cloud. It has been deployed in multiple clusters with tens of thousands of chips and is already serving more than 400 customers across industries, including State Grid, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, XPeng Motors, and Sina Weibo.

This isn’t a slide-deck chip, and it’s not an early pilot product either. It’s already been used in real production environments, accumulated real customer cases, and begun forming an ecosystem. More than six months ago, a friend told me, half casually, that T-Head’s in-house chips were “no worse than the mainstream solutions on the market.” At the time, I wasn’t fully convinced. Now, I more or less understand where that confidence came from.

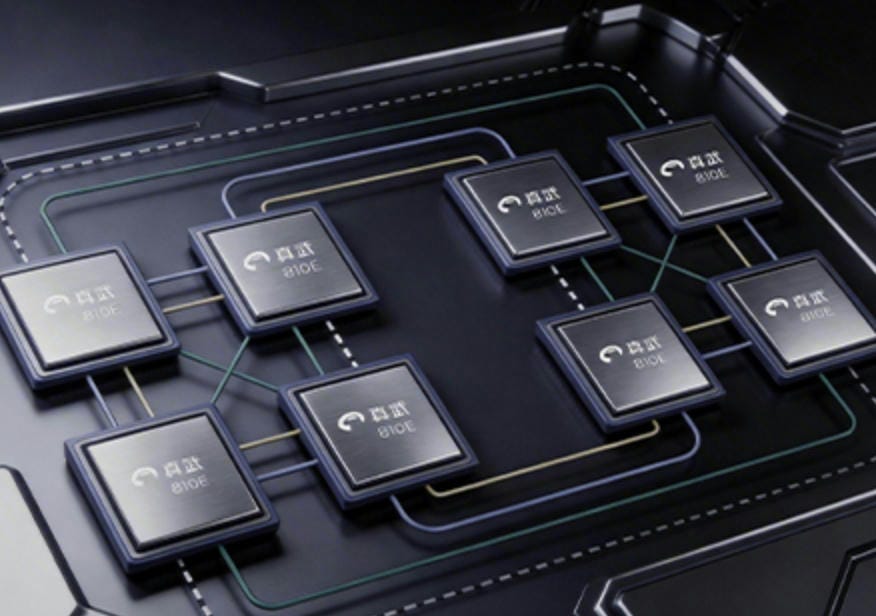

Based on what’s been disclosed so far, Zhenwu 810E’s technical profile is quite clear. It comes with 96GB of HBM2e memory, offers 700GB/s of inter-chip bandwidth, and is built on T-Head’s self-developed computing architecture and proprietary ICN (Inter-Chip Network) interconnect. On top of that, it runs on a fully in-house software stack, meaning both hardware and software are independently developed and fully owned.

The chip is designed for AI training, AI inference, and autonomous driving workloads. Judging from its key specs, many observers believe its overall performance is comparable to Nvidia’s H20, and in some respects superior to constrained models like the A800. There are even suggestions that a future upgraded version could approach — or potentially exceed — the performance of Nvidia’s A100. More importantly, Zhenwu is already being used in the training and inference pipelines of Alibaba’s Qwen large language models. That means this isn’t theoretical capability — it has already been tested in some of the most demanding AI workloads.

The name “Zhenwu” wasn’t chosen casually. In Chinese tradition, it carries real historical weight, which makes it an interesting choice for a high-end AI chip.

Zhenwu refers to Zhenwu the Great Emperor, also known as the Dark Heavenly Emperor. The figure took shape as early as the Wei–Jin and Northern–Southern Dynasties and later rose to a very high status within Daoism. Zhenwu is associated with ideas like guardianship, protection, restoring order, and using strength to suppress chaos. He’s not an aggressive, front-line figure, but more of a steady force that holds the system together from behind the scenes. That symbolism maps surprisingly well onto an AI chip, which isn’t user-facing but sits at the very foundation of the entire AI stack.

Historically, “Zhenwu” is also linked to long-term endurance and strength built over time, rather than quick wins. That mirrors T-Head’s chip journey — years of heavy investment and quiet work, but once the foundation is in place, it’s hard to dislodge.

From my own perspective, Zhenwu is clearly more than capable when it comes to AI inference, and within a certain range it looks quite cost-effective. As for training, the publicly available information is still limited, but it feels more like a matter of timing than a fundamental capability gap. If future versions of Qwen end up being partially — or even fully — trained on PPUs, that wouldn’t be surprising at all. Of course, such a transition would be complex and gradual; no one should expect it to happen overnight.

Against the backdrop of long-term U.S. restrictions on advanced computing power and persistent shortages of high-end chips inside China, Zhenwu’s debut is about far more than a single product launch. It signals that China’s AI industry now has more options, more flexibility, and a higher share of domestically developed computing power. T-Head has been around since 2018, and Zhenwu represents the result of nearly eight years of sticking to a difficult, self-developed path. It hasn’t been easy, but once the flywheel really starts spinning, the long-term upside could be enormous.

That said, focusing only on the chip itself misses the bigger picture. AI is a long value chain. From upstream computing hardware, to midstream cloud platforms, to downstream foundation models, you really need strong capabilities across all three layers to claim full-stack strength. Globally, there are very few companies that can credibly say they have this. In fact, there are basically two: Google and Alibaba.

Google’s case is already well known. Its TPU chips are mature and widely used, including by external customers. Google Cloud has been growing rapidly, with AI contributing a large share of incremental revenue. Meanwhile, Gemini has made dramatic progress over the past year, increasingly closing the gap with — and in some areas challenging — GPT. What really sets Google apart is how these pieces reinforce each other. TPUs lower the cost of training and running Gemini, Gemini and Google Cloud together form a powerful AI-plus-cloud ecosystem, and the success of both becomes the best possible advertisement for TPUs. This full-stack approach is a big reason why Google went from looking vulnerable in 2023 to being firmly on the front foot by 2025.

By contrast, Amazon and Microsoft have taken more partial approaches. Amazon’s Trainium chips have some technical merit but still lag well behind TPUs, and its external customer ecosystem is limited. Its foundation-model strategy relies heavily on investments in companies like Anthropic. Microsoft goes even further in that direction: its chip efforts remain modest, and its foundation-model capabilities depend almost entirely on OpenAI. Both giants focus their resources on the cloud layer, while leaning on partnerships and investments for chips and models. It’s a smart and efficient strategy — but it also means weaker control over the full AI stack.

Alibaba, like Google, chose the harder road: full-stack, in-house development. On the model side there’s Tongyi Lab, on the platform side Alibaba Cloud, and on the hardware side T-Head. Together they form what many in the industry call Alibaba’s AI “golden triangle.” This approach requires massive investment, long development cycles, and concentrated risk. But if it works, the payoff is huge, and the competitive moat is extremely hard to breach. In many ways, Google’s turnaround from uncertainty in 2023 to dominance in 2025 shows just how powerful full-stack control can be.

On the cloud side, Alibaba Cloud’s credentials hardly need explanation. It stands alongside AWS, Azure, and GCP as one of the world’s four major public cloud platforms, with infrastructure spanning 29 regions and more than five million customers. Its self-developed “Feitian” system remains China’s only homegrown cloud operating system. When Alibaba’s leadership talked in 2025 about building a “super AI cloud” — one of only five or six such platforms globally — that ambition wasn’t unrealistic from a technical or infrastructure standpoint.

On the model side, Qwen has become one of the most widely used foundation models in China’s enterprise market, and its open-source versions are among the most discussed on platforms like Hugging Face. Singapore’s national AI program even moved away from Meta’s LLaMA in favor of Qwen’s open architecture — a decision that speaks volumes about its maturity and openness.

Before today, the chip layer was the biggest question mark. Many people in China’s AI community told me that T-Head was already among the top tier of domestic AI chipmakers, possibly even the most advanced. But without concrete data, that was hard to assess. Now that Zhenwu’s specifications and deployments are public, it’s difficult to dispute T-Head’s leading position among Chinese AI chip players.

2025 was widely seen as the breakout year for Google’s TPU, driven by Gemini’s success. A similar dynamic could easily play out for T-Head. The stronger Qwen becomes, and the more it relies on PPUs, the more attractive Zhenwu and its successors will be. External customers can start by renting PPU compute through Alibaba Cloud and later decide whether to purchase chips directly. Over time, both cloud-delivered compute and direct chip sales could grow in parallel, steadily pushing down per-token costs and reinforcing a virtuous ecosystem cycle.

At this point, Alibaba’s AI golden triangle is firmly in place. From here on, analyzing Alibaba’s AI strategy in isolated pieces no longer makes sense — it needs to be viewed as an integrated whole. Everyone talks about building AI ecosystems, but in China at least, Alibaba is the only company that has actually built a comprehensive, fully self-developed, and internally coordinated AI stack. Humanity is only at the very beginning of the AI era, and the long march toward AGI has barely started. What Alibaba’s ecosystem will mean for the global AI industry over the next five, ten, or more years is still an open question — but one thing is clear: the impact will be profound.

Very insightful, thank you