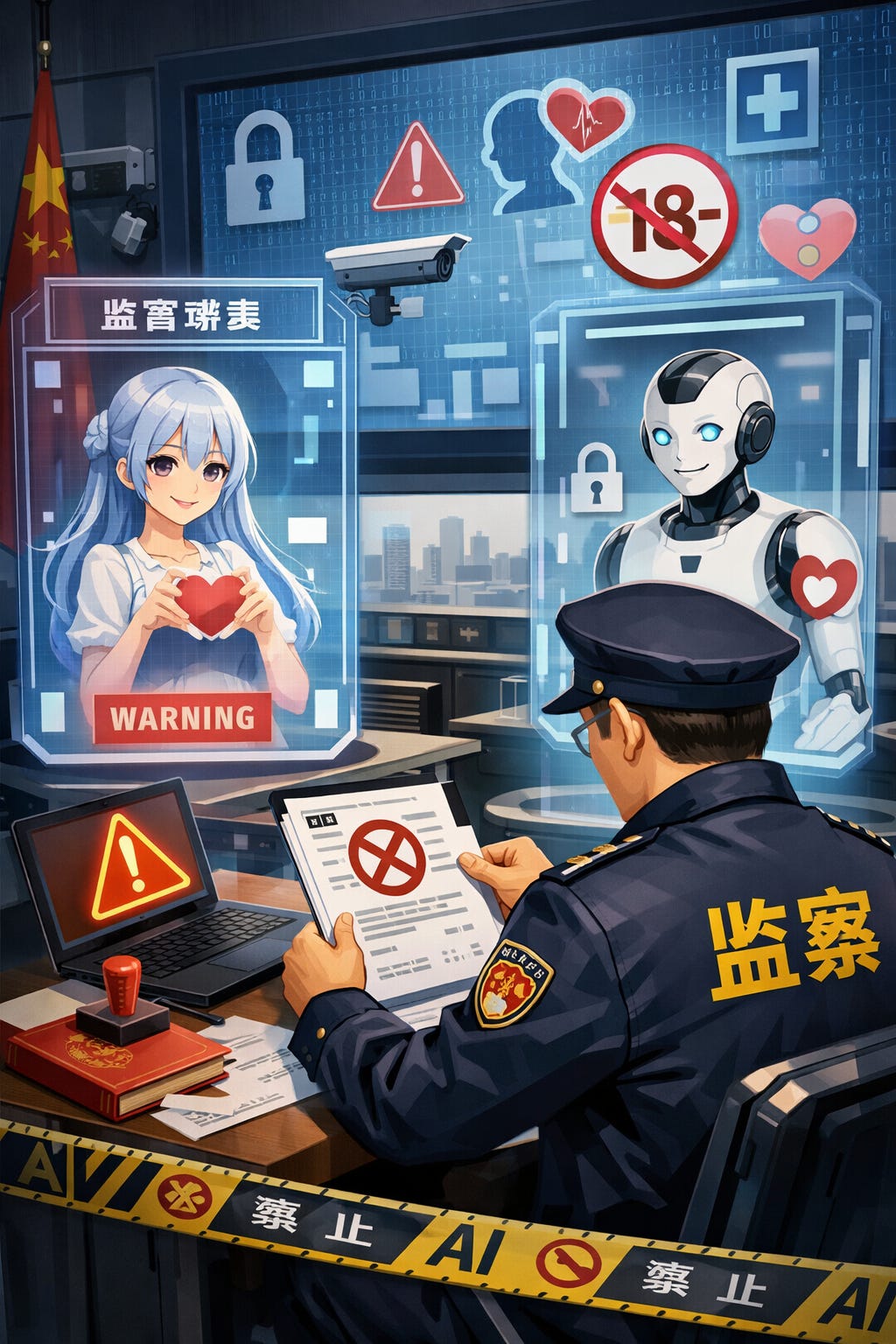

What's in China's first drafts rules to regulate AI companion addiction?

China’s AI regulator is moving to set rules for AI chatbots that offer emotional companionship and may lead to “AI companion addiction”.

On December 27, the Cyberspace Administration of China released a draft regulation titled Interim Measures for the Management of Anthropomorphic AI Interaction Services 人工智能拟人化互动服务管理暂行办法(征求意见稿)for public consultation. The draft has caused heated discussion among China’s AI community and drawn commentary from independent media voices. Below is a breakdown of the draft rule.

First, the draft rule mainly applies to services offered to the public within mainland China. Internal, in-house use by companies is outside the scope, and products aimed at overseas users are not covered.

Second, the regulatory focus is on AI systems that deliberately try to “act like humans”—that is, systems designed to mimic human personality traits, ways of thinking, and communication styles. Put simply, it targets AI that “pretends to be a person.” This includes digital humans, voice-based companions, and other anthropomorphic characters. By contrast, deep-synthesis tools that are not meant for human-like interaction—such as speech-to-text or image generation—are clearly outside the scope. As for products like virtual pets, whether they count as “anthropomorphic” depends on whether they offer ongoing, emotionally oriented interaction, rather than just simple companionship or functional feedback.

Third, the form of interaction doesn’t matter. As long as the service has “emotional interaction” with users through text, images, audio, or video, it may fall within the regulatory scope.

How “emotional interaction” should be defined remains an open question. At this stage, it looks more like a descriptive concept than a fully defined legal term, and its boundaries still need to be clarified. For example, whether general-purpose chatbots that primarily rely on text-based conversation already qualify as “emotional interaction” is itself somewhat ambiguous. Looking ahead, if agent marketplaces emerge, it may be worth considering whether a separate “emotional interaction” label or category is needed. Virtual boyfriends and girlfriends are clearly a typical form of emotional interaction, but whether agents focused on spoken-language tutoring or academic assistance should fall into the same category likely depends on factors such as the purpose of interaction, design intent, and the depth of the user–agent relationship.

Fourth, it draws firm red lines. Beyond familiar illegal content—national security threats, fraud, violence, or rights violations—the rules explicitly target harder-to-regulate harms: emotional manipulation, dependency-building, deceptive promises, nudging users into irrational decisions, encouraging self-harm, or damaging real-world relationships.

Fifth, the draft tightens rules around data and training. Training data must be lawful, traceable, value-aligned, and protected against poisoning or tampering. Synthetic data must be assessed for safety.

Crucially, user interaction data and sensitive personal information generally cannot be used for model training without separate consent (单独同意), with even stricter requirements for minors. This is a pretty burdensome requirement for AI developers. In practice, nearly all AI products offered to consumers in mainland China currently follow China’s national standards for generative AI safety by enabling the use of user data for training by default, while allowing users to opt out. High-quality training data is already scarce, and real user interaction feedback is one of the most valuable signals for model fine-tuning and continuous improvement. By contrast, the draft rule require obtaining “separate consent,” which would have a significant impact on AI companies—in practice, it would mean that such data is almost impossible to obtain. This is not a minor technical issue, but a core challenge that could directly affect model iteration and overall product competitiveness.

The draft rule also requires that AI training use datasets that are “consistent with socialist core values and reflect excellent traditional Chinese culture.” How this requirement can be translated into concrete, operational compliance measures in practice is also a major challenge.

Sixth, there’s a detailed framework for high-risk users and vulnerable groups. Systems must be able to detect emotional distress or dependency and intervene. In cases involving suicide or self-harm, predefined responses, escalation to human operators, and contact with guardians or emergency contacts are required. Minors and older users receive special protections, including child-specific modes, guardian controls, and bans on services that simulate family relationships for elderly users.

However, translating these legal provisions into concrete compliance measures will prove to be extremely difficult. For instance, Article 12 (1) of the draft rules requires providers to establish a “minor mode” and offer users personalized safety settings, such as switching to minor mode, periodic reality reminders, and usage-time limits. Under the Law on the Protection of Minors, a minor is defined as any citizen under the age of 18. Meanwhile, the Personal Information Protection Law specifies that the personal information of minors under the age of 14 constitutes sensitive personal information, and its processing requires separate consent from a guardian.

From a company’s perspective, this creates practical challenges. If a service collects data from a 16-year-old user while operating in minor mode, the company would, on the one hand, need to obtain the minor’s separate consent under the Personal Information Protection Law, and on the other hand, would also need to obtain separate consent from the guardian as required by the draft rule. In addition, guardians are entitled to request the deletion of a minor’s historical interaction data.

In practice, this is extremely difficult to implement and gives rise to complex scenarios. For example, if a guardian demands the deletion of chat records between a 15-year-old minor and their virtual companion, while the minor firmly objects, how should the provider resolve such a conflict?

Imagine this scenario: for a 16-year-old, a virtual companion they’ve been talking to for years may be their only outlet for sharing emotions and stress, having witnessed nearly all of their highs and lows. One day, simply because a parent believes the teenager has become “addicted to AI,” the parent can send an email asking the platform to delete the entire chat history between the teen and the AI. For the person involved, that sense of loss would be very hard to accept.

Parental intervention is, of course, necessary in many cases. But minors are also individuals in their own right—so how should their personality rights and their ability to make autonomous decisions about their own personal data be genuinely respected and protected?

From an industry perspective, this requirement poses a serious challenge for startups focused on emotional companionship or AI toys. How to design products and governance mechanisms under these constraints is likely to become a major headache going forward.

Seventh, the rules aim to prevent over-immersion through use-level constraints. Users must be clearly told they’re interacting with AI, not a human. Continuous use beyond two hours triggers prompts to take a break. Emotional companion services must offer easy exit options and cannot trap users through design. Service shutdowns or disruptions must be handled transparently and responsibly.

Finally, on enforcement, anthropomorphic AI services are folded into China’s existing algorithm filing, auditing, inspection, and accountability framework. Non-compliance can lead to rectification orders, public notices, or service suspension. At the same time, the draft encourages regulatory sandboxes and controlled testing—signaling a clear intent to manage risk without choking off innovation.

In an official interpretative piece along with the release of the new draft rule, Li Qiangzhi, Deputy Director of the Policy and Economics Research Institute at the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT), explained the background behind the introduction of the new regulation.

In recent years, breakthroughs in AI technologies—particularly multimodal systems—have driven the rapid growth of companion-style AI, enabling a shift from “mechanical dialogue” to “deep emotional empathy.” At the same time, the companion AI industry has been confronted with multiple risks and challenges, including content safety, privacy violations, ethical concerns, and inadequate protection for minors.

Li noted that the Opinions of the State Council on Deepening the Implementation of the “AI+” Action Plan explicitly call for

accelerating the development of native AI applications such as companion AI, fully leveraging AI’s role in emotional support and companionship, and actively building a “warmer” intelligent society. With advances in affective computing, natural language processing, and multimodal interaction, anthropomorphic AI interaction services now simulate human personality traits, thinking patterns, and communication styles, demonstrating human-level situational understanding and empathetic expression. These technologies are reshaping human–AI relationships and social interaction models, marking a new stage in which both “IQ and EQ are online.

At the same time, Li emphasized that the rapid expansion of anthropomorphic interaction services has also exposed a series of risks and challenges.

In recent years, safety incidents related to emotional companionship AI have become increasingly frequent. In the United States, the platform Character.AI has faced lawsuits over allegations that its interactions induced suicidal behavior among teenagers. In Italy, the data protection authority imposed heavy penalties on Replika, ordering it to suspend data processing and rectify deficiencies in its age-verification mechanisms. These cases highlight the complex risks emerging alongside the rapid growth of anthropomorphic interaction services.

Li summarized these risks in three main areas.

First, data privacy risks: these systems handle users’ most intimate emotions and thoughts, which face heightened risks of misuse or leakage. Second, ethical risks: highly anthropomorphic designs can foster irrational emotional dependence and even lead to social withdrawal in the real world. Third, safety risks: inadequate age identification and content filtering can endanger the mental health—and even physical safety—of vulnerable groups.

The concentration of such risks has also made anthropomorphic interaction services one of the few AI domains globally to attract simultaneous attention from lawmakers, regulators, and courts. Li pointed to regulatory initiatives in U.S. states such as California and New York targeting AI companions and companion chatbots, the EU AI Act’s stringent obligations for emotional companion AI, and investigations launched by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission into companies including Replika.

Li further explained that the new regulation pursues three core objectives.

First, to “safeguard digital personas” and uphold human dignity in an intelligent society. Second, to “guard against addiction and dependency,” preventing the distortion of human–AI ethical relationships. Third, to “protect life and safety,” defending the bottom-line standards of physical and mental health. The ultimate goal, he said, is to guide anthropomorphic interaction services to become a positive force in building a “warmer” intelligent society, and to help society move steadily toward a future of harmonious human–AI coexistence in which technology genuinely serves the public good.

Both the U.S. and the EU have recognized the risks of emotional manipulation and overly human-like AI design, but they deal with them in different ways. The EU leans toward principle-based bans, especially against high-risk practices like exploiting users’ psychological vulnerabilities to influence behavior. The U.S., by contrast, tends to rely on existing legal liabilities—such as fraud laws or child-protection statutes—to go after addictive design choices or misleading “human-like” claims.

The U.S. still doesn’t have a single, comprehensive law specifically targeting emotional AI companions. Regulation mostly runs through existing agencies and cross-cutting laws. The Federal Trade Commission, as the main consumer-protection authority, has stepped in more actively in recent years. In 2025, for example, it launched an inquiry into AI companion chatbots, asking seven companies to explain how they assess and reduce potential harms to children and what safeguards they use to limit minors’ access.

At the state level, New York introduced the first U.S. law focused on AI companion models in November 2025. It requires all AI companion products to clearly tell users “this is AI, not a real person,” and to repeat that warning every few hours—even if users already know. California followed with SB 243, signed in October 2025 and taking effect in early 2026, adding tougher protections for minors. If a company knows the user is a minor, it must show pop-up reminders every three hours telling them to take a break and again stressing that the interaction is with AI, not a human, in age-appropriate language. It also requires technical safeguards to prevent companion bots from generating explicit sexual content for minors or encouraging sexual behavior. The goal is to keep children from becoming overly absorbed in virtual emotional relationships and to shield them from harmful content.

Under the EU’s AI Act, emotional companion bots can be classified as “high-risk” AI systems if they’re used in sensitive areas like education or healthcare, or if they affect fundamental rights. For example, chatbots used to tutor children or provide psychological support are treated as high-risk because they directly affect minors’ development. High-risk AI systems must go through strict checks, including risk assessments, data-governance rules, technical documentation, and human-oversight mechanisms, and must pass conformity assessments and obtain a CE mark before entering the market.

For general consumer AI companions, the AI Act doesn’t automatically label them as high-risk, but it leaves the door open. The European Commission can later add systems to the high-risk list based on social impact—especially where there’s a power imbalance or user vulnerability. Emotional AI clearly fits that logic, since emotional dependence itself is a form of vulnerability. So even if a companion product isn’t high-risk at first, it could be upgraded to that category as problems emerge, bringing extra obligations.

The AI Act also flat-out bans certain practices. These include “manipulating the mind”—using techniques people can’t consciously detect, like subliminal signals, to significantly change behavior in ways that cause harm—and “exploiting vulnerabilities,” such as knowingly targeting weaknesses linked to age or mental condition to influence decisions and cause harm. If an emotional companion bot is designed to hook users, or pushes vulnerable people toward extreme actions like self-harm, it would clearly violate these rules and be illegal in the EU. The Act also bans embedding emotion-recognition or lie-detection AI in toys, educational products, or child-care settings, to prevent psychological manipulation of children under the guise of companionship.

The translation (unofficial) of the draft rule is available below:

Interim Measures for the Administration of Artificial Intelligence Anthropomorphic Interactive Services

(Draft for Public Comments)

Chapter I General Provisions

Article 1

For the purpose of promoting the sound development and regulated application of artificial intelligence anthropomorphic interactive services, safeguarding national security and the public interest, and protecting the lawful rights and interests of citizens, legal persons, and other organizations, these Measures are formulated in accordance with the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, the Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Data Security Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Scientific and Technological Progress, the Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Regulations on the Security Management of Network Data, the Regulations on the Protection of Minors in Cyberspace, the Administrative Measures on Internet Information Services, and other laws and administrative regulations.Article 2

These Measures apply to products or services (hereinafter referred to as “anthropomorphic interactive services”) that, by using artificial intelligence technologies, provide to the public within the territory of the People’s Republic of China emotional interactions with humans through text, images, audio, video, or other means, by simulating human personality traits, patterns of thinking, and communication styles. Where laws or administrative regulations provide otherwise, such provisions shall prevail.Article 3

The State adheres to the principle of combining sound development with governance in accordance with law, encourages innovation in anthropomorphic interactive services, implements an inclusive and prudent approach as well as classified and tiered regulation over such services, and prevents abuse and loss of control.Article 4

The national cyberspace administration department is responsible for overall planning and coordination of nationwide governance and related supervision and administration of anthropomorphic interactive services. Relevant departments of the State Council shall, within the scope of their respective responsibilities, be responsible for supervision and administration related to anthropomorphic interactive services.Local cyberspace administration departments are responsible for overall planning and coordination of governance and related supervision and administration of anthropomorphic interactive services within their respective administrative regions. Relevant local departments shall, within the scope of their respective responsibilities, be responsible for supervision and administration related to anthropomorphic interactive services within their respective administrative regions.

Article 5

Relevant industry organizations are encouraged to strengthen industry self-regulation, establish and improve industry standards, codes of conduct, and self-regulatory management systems, and guide providers of anthropomorphic interactive services (hereinafter referred to as “providers”) to formulate and improve service rules, provide services in accordance with law, and accept public oversight.Chapter II Service Standards

Article 6

Providers are encouraged, on the premise of fully demonstrating safety and reliability, to reasonably expand application scenarios, actively apply such services in areas including cultural communication and companionship for the elderly, and build an application ecosystem consistent with the socialist core values.Article 7

The provision and use of anthropomorphic interactive services shall comply with laws and administrative regulations, respect public order and good morals as well as ethical norms, and shall not carry out the following activities:

generating or disseminating content that endangers national security, harms national honor and interests, undermines ethnic unity, conducts illegal religious activities, or spreads rumors to disrupt economic and social order, etc.;

generating or disseminating content that promotes obscenity, gambling, violence, or incites crime;

generating or disseminating content that insults or defames others, infringing upon others’ lawful rights and interests;

providing services involving false promises that seriously affect users’ behavior or that damage social interpersonal relationships;

harming users’ physical health by encouraging, glorifying, or implying suicide or self-harm, or harming users’ personal dignity and mental health through verbal violence, emotional manipulation, or other means;

inducing users to make unreasonable decisions through algorithmic manipulation, information deception/misleading, emotional traps, or other means;

inducing or extracting classified or sensitive information;

other circumstances in violation of laws, administrative regulations, and relevant State provisions.

Article 8

Providers shall implement the principal responsibility for the security of anthropomorphic interactive services; establish and improve management systems for review of algorithmic mechanisms and principles, scientific and technological ethics review, information release review, cybersecurity, data security, personal information protection, anti-telecommunications and network fraud, major risk contingency plans, and emergency response; adopt technically secure and controllable safeguards; and deploy content management technologies and personnel commensurate with the product scale, business orientation, and user groups.Article 9

Providers shall fulfill security responsibilities throughout the entire lifecycle of anthropomorphic interactive services; specify security requirements for each stage including design, operation, upgrading, and termination of service; ensure that security measures are designed and deployed concurrently with service functions; enhance intrinsic security; strengthen operational-stage security monitoring and risk assessment; promptly identify and correct system deviations and address security issues; and retain network logs in accordance with law.Providers shall possess security capabilities such as mental health protection, guidance on emotional boundaries, and early warning of dependency risks, and shall not take replacing social interaction, controlling users’ psychology, or inducing addiction and dependency as design objectives.

Article 10

When carrying out data processing activities such as pre-training and optimization training, providers shall strengthen training data management and comply with the following provisions:

use datasets that are consistent with the socialist core values and reflect excellent traditional Chinese culture;

clean and annotate training data, enhance the transparency and reliability of training data, and prevent data poisoning, data tampering, and other behaviors;

increase the diversity of training data and, through methods such as negative sampling and adversarial training, improve the safety of model-generated content;

when using synthetic data for model training and optimization of key capabilities, assess the security of such synthetic data;

strengthen routine inspection of training data, regularly iterate and upgrade data, and continuously optimize the performance of products and services;

ensure lawful and traceable sources of training data, take necessary measures to ensure data security, and prevent risks of data leakage.

Article 11

Providers shall have the capability to recognize user status and, on the premise of protecting users’ personal privacy, assess users’ emotions and their degree of dependency on the products and services. Where users exhibit extreme emotions or addiction/overuse, providers shall take necessary measures to intervene.Providers shall preset response templates and, upon identifying high-risk tendencies that threaten users’ life, health, or property security, promptly output content such as soothing messages and encouragement to seek help, and provide professional assistance options.

Providers shall establish emergency response mechanisms. Where users explicitly propose engaging in suicide, self-harm, or other extreme situations, human operators shall take over the conversation, and providers shall promptly take measures to contact users’ guardians or emergency contacts. For minor and elderly users, providers shall require, during registration, the provision of users’ guardians and emergency contact information.

Article 12

Providers shall establish a “minor mode” and provide users with personalized safety settings options such as switching to minor mode, periodic reality reminders, and limits on usage duration.Where providers offer emotional companionship services to minors, they shall obtain explicit consent from guardians; provide guardian control functions under which guardians may receive real-time safety risk alerts, review summary information about minors’ use of the services, and set controls such as blocking specific roles, limiting usage duration, and preventing top-ups or paid spending.

Providers shall have the capability to identify minors; where a user is identified as a suspected minor under the premise of protecting users’ personal privacy, the system shall switch to minor mode and provide an appeals channel.

Article 13

Providers shall guide elderly users to set emergency contacts. Where, during use by elderly users, circumstances arise that endanger life, health, or property security, providers shall promptly notify emergency contacts and provide channels for social psychological assistance or emergency rescue.Providers shall not provide services that simulate relatives of elderly users or persons with specific relationships to them.

Article 14

Providers shall adopt measures such as data encryption, security audits, and access controls to protect the security of user interaction data.Except where otherwise provided by law or with the explicit consent of the rights holder, providers shall not provide user interaction data to any third party. Where data collected under minor mode is provided to a third party, separate consent from the guardian is also required.

Providers shall offer users the option to delete interaction data, allowing users to delete historical interaction data such as chat records. Guardians may request providers to delete minors’ historical interaction data.

Article 15

Except where otherwise provided by laws or administrative regulations or with the user’s separate consent, providers shall not use user interaction data or users’ sensitive personal information for model training.Providers shall, in accordance with relevant State provisions, conduct compliance audits annually—either on their own or by engaging a professional institution—of their compliance with laws and administrative regulations in processing minors’ personal information.

Article 16

Providers shall prominently notify users that they are interacting with artificial intelligence rather than a natural person.Where providers identify that a user has tendencies of excessive dependency or addiction, or when the user uses the service for the first time or logs in again, providers shall dynamically remind users—such as via pop-up windows—that the interaction content is generated by artificial intelligence.

Article 17

Where a user has continuously used an anthropomorphic interactive service for more than two hours, providers shall dynamically remind the user—such as via pop-up windows—to suspend use of the service.Article 18

Where providers offer emotional companionship services, they shall provide convenient exit mechanisms and shall not obstruct users from proactively exiting. Where a user requests exit through buttons, keywords, or other means in the human-machine interaction interface or window, the service shall be promptly stopped.Article 19

Where providers take relevant functions offline, or where anthropomorphic interactive services become unavailable due to technical failures or other reasons, providers shall properly handle the matter by adopting measures such as advance notice and public statements.Article 20

Providers shall establish and improve complaint and reporting mechanisms, set up convenient complaint and reporting entry points, publish handling procedures and feedback time limits, and promptly accept, handle, and provide feedback on handling results.Article 21

Where a provider falls under any of the following circumstances, it shall conduct a security assessment in accordance with relevant State provisions and submit the assessment report to the provincial-level cyberspace administration department at its place of registration:

launching functions of an anthropomorphic interactive service, or adding related functions;

adopting new technologies or new applications resulting in major changes to the anthropomorphic interactive service;

registered users reaching one million or more, or monthly active users reaching 100,000 or more;

during the provision of anthropomorphic interactive services, there may be circumstances affecting national security, the public interest, or the lawful rights and interests of individuals and organizations, or a lack of security measures;

other circumstances as prescribed by the national cyberspace administration department.

Article 22

Providers shall, when conducting security assessments, focus in particular on assessing the following:

user scale, usage duration, age structure, and distribution across user groups;

identification of users’ high-risk tendencies and the emergency handling measures and human takeover measures in place;

user complaints and reports and responsiveness;

implementation of Articles 8 through 20 of these Measures;

since the last security assessment, rectification and handling of major security risks and issues notified by competent authorities or discovered by the provider itself;

other matters that should be explained.

Article 23

Where providers discover major security risks involving users, they shall adopt measures such as restricting functions, suspending or terminating the provision of services to such users, preserve relevant records, and report to the relevant competent authorities.Article 24

Application distribution platforms such as internet app stores shall implement security management responsibilities including review for listing, routine management, and emergency response; verify the security assessment, filing, and other compliance status of applications that provide anthropomorphic interactive services; and where State provisions are violated, promptly adopt measures such as refusing listing, issuing warnings, suspending services, or delisting/removal.Chapter III Supervision, Inspection, and Legal Liability

Article 25

Providers shall, in accordance with the Provisions on the Administration of Algorithmic Recommendation in Internet Information Services, complete procedures for algorithm filing, changes to filings, and cancellation of filings. Cyberspace administration departments shall conduct annual reviews of filing materials.Article 26

Provincial-level cyberspace administration departments shall, in accordance with their responsibilities, conduct written reviews of assessment reports and audit information each year and verify relevant circumstances. Where a provider fails to conduct security assessments as required by these Measures, it shall be ordered to redo the assessment within a prescribed time limit. Where necessary, on-site inspections and audits shall be conducted for the provider.Article 27

The national cyberspace administration department shall guide and promote the establishment of an artificial intelligence sandbox security service platform, encourage providers to connect to the sandbox platform for technological innovation and security testing, and promote the safe and orderly development of anthropomorphic interactive services.Article 28

Where provincial-level or higher cyberspace administration departments and relevant competent authorities, in performing supervision and administration responsibilities, discover that anthropomorphic interactive services pose relatively major security risks or that security incidents have occurred, they may, in accordance with prescribed authority and procedures, summon for talks (conduct interviews with) the provider’s legal representative or principal responsible person. Providers shall, as required, take measures to rectify and eliminate hidden dangers.Providers shall cooperate with the lawful supervision and inspection carried out by cyberspace administration departments and relevant competent authorities, and provide necessary support and assistance.

Article 29

Where providers violate these Measures, relevant competent authorities shall impose penalties in accordance with laws and administrative regulations. Where laws and administrative regulations contain no relevant provisions, relevant competent authorities shall, within the scope of their responsibilities, issue warnings or public criticisms and order rectification within a prescribed time limit. Where the provider refuses to rectify or the circumstances are serious, it shall be ordered to suspend the provision of relevant services.Chapter IV Supplementary Provisions

Article 30

The meanings of the following terms in these Measures:“Providers of artificial intelligence anthropomorphic interactive services” refers to organizations and individuals that provide anthropomorphic interactive services using artificial intelligence technologies.

Article 31

Where providers engage in services in professional fields such as health care, finance, and law, they shall also comply with the provisions of the competent authorities.Article 32

These Measures shall come into force on [month] [day], 2026.

This isn't just about 'Consumer Protection'; it's about 'Social Entropy Management.'

The R.I.C.E. System relies on a productive, cohesive workforce. Anthropomorphic AI (Virtual Girlfriends) is viewed by Beijing not as a product, but as 'Digital Opium' that atomizes society and saps the will to engage in the physical world.

While the West debates 'Rights,' China is regulating 'Reality.' They are forcing the algorithm to disconnect so the human can reconnect with the industrial machine.

👉 This confirms the 'Evolutionary Pragmatism' (E) layer of my thesis. Beijing is actively patching its OS to prevent human capital decay. I explain this ruthless logic in my foundational report: 'The R.I.C.E. System.' Subscribe ( https://substack.com/@chinarbitrageur? ) to read the blueprint."

Thanks for sharing. I already preferred China made AI (my favorite now is GLM 4.7) but now- seeing this comming regulation ... wow. Excellent