Chinese Top Trade Expert: Facts and Analysis of the Recent U.S.–China Dispute over Export Controls

During the latest round of U.S.–China tensions, experts and scholars from both countries have engaged in extensive discussion. Notably, several Chinese experts have moved beyond simply reiterating the Ministry of Commerce spokesperson’s statements and instead provided in-depth professional analyses that help illuminate the policy logic behind what many in Washington view as China’s “disproportionate escalation.” Among these voices, the perspective of Professor Cui Fan of the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) stands out.

In a recent long post on his personal WeChat blog, Cui argued that following the United States’ September 29 decision to significantly expand its export controls on China through measures such as the “50 percent ownership rule,” China’s October 9 response—introducing moderate extraterritorial jurisdiction under Article 49 of the Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items and adopting a similar “50 percent rule” in its rare-earth export controls—was a reciprocal response rather than an escalation. Compared with the United States’ broad, discriminatory, and highly unpredictable control regime, Cui noted, China’s approach is more restrained, non-discriminatory in principle, and takes into account the facilitation of legitimate trade.

Although debates over who is right and who is wrong will continue, the fact that scholars from both China and the United States are engaging in meaningful discussions on this issue is undoubtedly helpful for understanding recent developments in U.S.–China relations and for observing how events may unfold going forward.

Cui Fan is a Professor and Ph.D. advisor at UIBE’s School of International Trade and Economics. He also serves as Chief Expert of UIBE’s Hainan Research Institute, Director of the Research Department at the China Society for WTO Studies, and an Arbitrator at the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC). In addition, he participates in several policy advisory bodies, including the Global Value Chain Expert Group of the Ministry of Commerce’s Trade Policy Advisory Committee and the International Finance Research Expert Studio of the Ministry of Finance.

Cui holds a Ph.D. in Economics from UIBE and an LL.M. in International Business Law from the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is also a licensed lawyer and certified public accountant, with multiple professional qualifications in international trade and finance. His research focuses on international trade and economic rules, foreign investment regimes, China’s free trade zones and free trade ports, global value chains, and trade remedies. He has long studied the alignment between high-standard international trade rules and China’s opening-up policies. Over the years, he has led or participated in numerous national and ministerial-level research projects and published widely in both Chinese and English journals. A frequent commentator in the media on U.S.–China trade policy and WTO rule reform, Cui is widely regarded as one of China’s leading scholars in international economic law and trade policy.

Cui Fan: Facts and Analysis of the Recent U.S.–China Dispute over Export Controls

On September 29, 2025, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) published an interim final rule in the Federal Register, which stated that any company in which one or more entities on the Entity List (EL) or Military End User (MEU) List hold a combined stake of 50 percent or more will itself automatically be subject to the same restrictions. Ten days later, on October 9, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) released several new announcements related to export controls. Among them, Announcement No. 61, titled “Decision on Implementing Export Controls on Certain Overseas Rare Earth Items,” marked the first time the Ministry, with approval from the State Council, had exercised extraterritorial jurisdiction under Article 49 of the Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items. The announcement also introduced a 50 percent ownership rule, similar to the one issued by the United States on September 29.

This article aims to sort through the main facts behind the recent U.S.-China disputes over export controls, analyze the similarities and differences between the two systems, and outline how China has responded to U.S. pressure. Our view is that mutual dependence is the normal state of global trade and that mutual benefit and shared gains are at the heart of the U.S.-China economic relationship. The only effective way to handle differences and stabilize or improve economic relations is through equal consultation based on mutual respect.

So what exactly happened before October 9?

On April 2, the U.S. announced a so-called “reciprocal tariff” policy against countries and regions around the world, imposing a 34 percent tariff on Chinese goods while warning that any country taking retaliatory action would face additional punitive tariffs. Two days later, China announced its own 34 percent counter-tariff on U.S. imports. The U.S. then raised tariffs on Chinese goods twice, by a total of 91 percent, and China responded with matching countermeasures. Between May 10 and 11, Chinese and U.S. negotiators met in Geneva and issued a joint statement on May 12, in which both sides agreed to cancel the 91 percent additional tariffs and the corresponding retaliatory tariffs, to suspend the 24 percent reciprocal tariffs and China’s counter-tariffs for 90 days, and for China to suspend or cancel its non-tariff countermeasures imposed since April 2. For the remaining U.S. unilateral tariffs — the 10 percent reciprocal tariffs, the fentanyl-related tariffs, and the Section 301 tariffs — China maintained the right to apply corresponding countermeasures.

The day after the joint statement was released, on May 13, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued three “guidance documents.” The first declared that using Huawei’s Ascend chips anywhere in the world would be considered a violation of U.S. export control regulations. The second warned that using U.S. artificial intelligence chips to train or run Chinese AI models could carry potential consequences. The third provided guidance to U.S. companies on how to protect their supply chains from diversion tactics. Although these guidance documents were not formal laws or regulations, they clearly carried strong implications for how export controls would be enforced. Some industry experts saw this as a sign that the U.S. was stretching the limits of its extraterritorial jurisdiction under export control law. In practice, it also showed that Washington’s goal was not just to choke off the supply of technology to Chinese companies like Huawei, but also to curb market demand and restrict the broader ecosystem surrounding Chinese AI models.

China’s Ministry of Commerce quickly responded, issuing a harsh criticism of the measures at its regular press briefing on May 15. Perhaps realizing that its initial language was too strong, the U.S. quietly revised the wording in its press release, changing the phrase “using Huawei Ascend chips anywhere in the world violates U.S. export control laws” to a softer “warning the industry about the risks of using advanced Chinese computing chips, including certain Huawei Ascend models.” The actual contents of the guidance, however, remained unchanged. On May 19, China’s Ministry of Commerce again condemned the U.S. actions, saying that “Washington’s hand has stretched too far” and calling it “a typical act of unilateral bullying.” The spokesperson warned that if the U.S. insisted on continuing to harm China’s legitimate interests, China would take firm measures to defend its rights.

On May 23, the U.S. government announced new controls on ethane exports and immediately blocked three planned shipments to China. By the end of May, three major chip design software companies were notified by U.S. authorities to suspend providing software services or technical support to Chinese clients. Around the same time, Washington also paused export licenses that allowed American firms to sell products and technologies to China’s Commercial Aircraft Corporation (COMAC). Foreign media reported that these moves were part of a pressure campaign triggered by what the U.S. saw as China’s slow progress in resuming rare earth exports.

Against this backdrop, the Chinese and U.S. presidents spoke by phone on June 5 and agreed to continue implementing the Geneva consensus. Following their call, Chinese and U.S. economic teams met again in London on June 9 and 10, where they reached what became known as the “London Framework.” The U.S. Commerce Secretary, who oversees export control policy, personally attended the talks. Under the framework, China agreed to review and approve qualified export license applications in accordance with its laws, while the U.S. would remove a series of restrictive measures imposed on China. This meeting was significant because, before London, Washington had long insisted that export controls were purely national security matters that could not be negotiated. The London talks likely marked the first time in the history of U.S.-China negotiations that Washington gave some kind of response to Beijing’s concerns about its own export control regime.

On July 10, NVIDIA founder and CEO Jensen Huang met with U.S. President Donald Trump. Two days later, Huang traveled to China and revealed that the U.S. government was preparing to begin issuing export licenses for NVIDIA’s H20 chip, a downgraded version designed specifically for the Chinese market that had been barred from export in April. NVIDIA’s official website confirmed the same news on July 14. However, once the possibility of approval became public, several members of Congress voiced strong opposition. On July 15, Representative John Moolenaar told POLITICO that he supported maintaining the previous restrictions, and on July 18, Reuters reported that Moolenaar had sent a letter to the Commerce Secretary criticizing the administration’s plan to approve H20 exports. Then, on July 28, five senators — including Mark Warner — also wrote to the Commerce Department, urging it to block the plan.

Amid these debates, Washington saw a surge of legislative activity around chip security. Several lawmakers pushed forward the CHIPS Security Act, which was introduced in both the House and the Senate in May. The House version was co-sponsored by physicist and congressman Bill Foster, while the Senate version was led by Senator Tom Cotton. The bill set out two key requirements: within 180 days of enactment, exported integrated circuits would need to include built-in identification and tracking systems; and within a year, they would also need a “remote shutdown” feature to prevent unauthorized use. Reports suggested that as early as 2024, U.S. think tanks had already floated a broader idea known as “on-chip governance mechanisms,” essentially a hardware-level backdoor system.

Then, on August 10, the Financial Times reported that NVIDIA and AMD had agreed to hand over 15 percent of their chip sales revenue from China to the U.S. government — effectively creating a China-specific export tax that would ultimately be paid by Chinese buyers. Finally, on August 25, Representative Moolenaar wrote another letter to the Commerce Secretary proposing a new regulatory framework called the “Rolling Technical Threshold,” or RTT. Under this approach, the performance ceiling for U.S. chip exports to China would no longer be linked to America’s own technological capabilities, but rather to China’s. Each time the U.S. approved a new chip for export, it would be designed to stay just slightly ahead of the best chip China could produce domestically. The goal was to squeeze the market space for Chinese chipmakers while keeping China’s overall computing capacity below 10 percent of that of the United States. In short, it was a strategy meant to keep China dependent on U.S. hardware while restricting the growth of its advanced AI capabilities.

From my observation, it seems that sometime between July and August, the Chinese government’s focus on the chip issue began to shift. Initially, Beijing appeared hopeful that Washington might ease or even lift some export restrictions. But as the months went on and new signals kept coming from the U.S., that optimism gradually faded. Instead, China started placing greater emphasis on chip security and on shielding its domestic semiconductor firms from the impact of U.S. competition.

On July 28 and 29, Chinese and U.S. officials met in Stockholm for another round of talks. The outcome was modest: the two sides agreed, in a joint statement on August 12, to extend for another 90 days the suspension of the 24 percent tariffs that had been set to expire that day. However, there was no sign of progress on export control or related issues. To maintain communication on these topics—especially regarding TikTok—the two sides agreed that their economic and trade teams would meet again in Madrid on September 14–15. There, they reportedly reached a basic framework agreement to handle the TikTok issue through cooperative means, reduce investment barriers, and promote related areas of trade and economic collaboration.

But tensions quickly flared again. On September 12, just before the Madrid meeting, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced that it was adding 23 Chinese companies to its export control Entity List, including 13 firms in the semiconductor and integrated circuit sectors. The next day, September 13, China responded by launching an anti-dumping investigation into imports of analog chips from the United States and, at the same time, a non-discrimination investigation targeting U.S. measures against China’s semiconductor industry. The latter covered a wide range of discriminatory actions taken—or planned—by Washington since 2018.

Then, right after the Madrid talks ended, on September 16, the U.S. added another 11 Chinese entities to the Entity List. On September 25, China’s Ministry of Commerce fired back by placing three U.S. entities under export control measures and listing another three American companies on its Unreliable Entity List.

Four days later, on September 29, the U.S. Department of Commerce unveiled what it called the “50 percent ownership rule”—the same rule discussed earlier—which stipulates that any company at least half-owned by one or more entities already on the Entity List (EL) or Military End User (MEU) List would automatically fall under those same restrictions. This new rule caused the number of Chinese entities subject to U.S. controls to multiply several times over—from just over 1,100 to many thousands—dramatically increasing uncertainty for global trade and supply chains.

Beijing’s response was immediate. China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a strong statement condemning the move as “extremely malicious in nature,” adding that “China will take all necessary measures to resolutely defend the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese companies.” (See MOFCOM’s response to reporters on the BIS’s new ownership-penetration rule.)

The very next day, September 30, the impact of the new rule was already visible. Under U.S. pressure and citing the so-called “50 percent rule,” the Dutch government ordered the freezing of management and operational rights of Nexperia, a semiconductor company owned by China’s Wingtech Technology. The case became an immediate and concrete example of how Chinese investors were being harmed by the new regulation.

Then, on October 8, the U.S. added another 16 mainland Chinese entities and three Hong Kong-registered addresses to the Entity List. In total, since the Madrid meeting, the U.S. had rolled out around 20 new restrictive measures against China.

And it’s worth noting that the actions mentioned above only cover U.S. export control measures. There were also other restrictions—like additional port fees imposed on Chinese shipping companies and vessels built in China—that tell their own long stories, which we won’t go into here.

Finally, on October 9, China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a new series of announcements strengthening and refining export controls on rare earths and other key materials.

2. Is China Escalating the Tensions?

After China introduced its new export control measures on October 9, Washington reacted with surprise. U.S. officials described the move as “out of the blue” and accused Beijing of escalating the conflict. But in truth, what’s really surprising is Washington’s surprise. Many companies—Chinese, American, and others—had already suffered losses from the endless stream of new U.S. restrictions. Even some U.S. firms complained that after the new “50 percent ownership rule” took effect, they could no longer determine whether their trading partners were affected and had no choice but to suspend transactions. Global supply chains were severely disrupted. Yet, for some in Washington, issuing new restrictions on China had become routine. They ignored Beijing’s repeated warnings and harsh statements, and then seemed shocked when China finally decided to respond in kind.

(1) Overview of the Chinese Ministry of Commerce’s Announcements Issued on October 9

On October 9, China’s Ministry of Commerce released seven separate announcements, all related to areas overseen by the Bureau of Security and Control. One of them added 14 American entities—some including their subsidiaries—to the Unreliable Entity List, imposing bans on trade and investment with China and prohibiting Chinese individuals and organizations from conducting transactions with them.

Four other announcements—MOFCOM Notices No. 55 through No. 58—jointly issued with the General Administration of Customs, placed a range of items under export control: superhard materials, certain medium and heavy rare earth products, rare-earth-related equipment and raw materials, and lithium batteries and synthetic graphite anode materials. These controls were to take effect on November 8.

Another announcement, Notice No. 62, added rare earth–related technologies to the Dual-Use Item Export Control List, also implementing immediate export restrictions. It’s worth noting that many of these technologies had already been included in China’s Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited or Restricted from Export. So what’s the difference this time?

Under the Regulations on Technology Import and Export Administration and the Catalogue of Technologies Prohibited or Restricted from Export, China’s tech export management framework has so far used cross-border transfer as the defining standard—meaning only transfers across borders were considered “exports.” But under export control law, the concept of a “technology export” is broader: it also covers situations where a technology is provided to foreign organizations or individuals, whether inside or outside China. This is what’s known as “deemed export.”

In that sense, Notice No. 62’s main significance lies in bringing rare-earth-related technologies under supervision for deemed export, aligning with Article 2 of China’s Export Control Law. Going forward, it’s clear that the system governing technology transfers under the Technology Import and Export Regulations and the export control framework under the Export Control Law will need stronger coordination. Relevant authorities have reportedly started studying reforms in this area. Once the revised Foreign Trade Law is finalized, revisions to the Technology Import and Export Regulations are expected to follow. In fact, the State Council’s 2025 Legislative Work Plan (Document No. 17) has already listed the Technology Import and Export Regulations as a preparatory item for amendment.

The move that drew the most U.S. criticism, however, was MOFCOM Notice No. 61, titled “Decision on Implementing Export Controls on Certain Overseas Rare Earth Items.” This was the measure that formally extended China’s export control jurisdiction beyond its borders—a concept known as extraterritorial jurisdiction (or “long-arm jurisdiction,” “extraterritorial application,” and other related terms).

According to Article 49 of the Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, “Where overseas organizations or individuals, outside the territory of the People’s Republic of China, transfer or provide the following goods, technologies, or services to specified countries, regions, organizations, or individuals, the Ministry of Commerce of the State Council may require the relevant operators to act in accordance with these Regulations: (1) dual-use items that are manufactured abroad containing, incorporating, or blended with specific dual-use items of PRC origin; (2) dual-use items manufactured abroad using PRC-origin technologies; or (3) specific dual-use items of PRC origin themselves.”

In other words, China’s export controls do not automatically apply extraterritorially to all items. Rather, the Ministry of Commerce may require such application within a certain scope. This reflects what might be called China’s policy of “measured extraterritorial jurisdiction.”

The October 9 decision to apply export controls extraterritorially to certain rare earth items represents China’s first concrete exploration and practice of such jurisdiction.

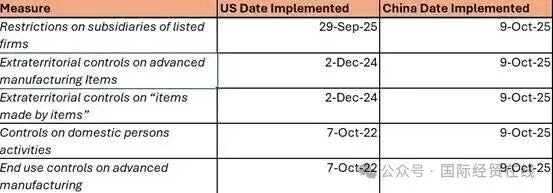

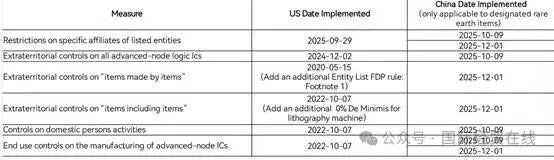

(2) China’s Export Control Measures Mirror What the U.S. Has Already Done

As U.S. technology policy expert Paul Triolo has pointed out, most of the measures China announced on October 9 were not innovations, but rather steps the United States had already taken years earlier. Only a small number of people in Washington’s policy and think-tank circles are willing to acknowledge this reality. There’s an old saying in English — “every accusation is a confession.” Every U.S. accusation that China is “weaponizing export controls” is, in a sense, an admission that Washington itself has long been doing exactly that — though few American officials seem to realize it. The double standard here could not be more obvious.

To illustrate his point, Triolo even made a comparison chart showing how each of China’s new rules corresponds to long-standing U.S. measures. When I first saw the chart, I found it quite convincing — but I also felt it left out some important details. So I reached out to a Chinese lawyer with extensive hands-on experience in export control cases and a former graduate student of mine, and asked him to help refine the chart. The Chinese lawyer happened to be traveling when I called, but just a few hours later, he sent me back a revised version. His table was much more detailed and did a better job of showing how the United States has, over the years, continually expanded and hardened its export control regime.

Because the table involves a number of highly technical details, I won’t translate or explain it line by line here. Instead, I’ll focus on a few key examples that best capture the broader picture.

The first item in the table refers to the 50 percent ownership rule we discussed earlier — the U.S. introduced it on September 29, and China incorporated the same logic into MOFCOM Notice No. 61 on October 9.

The third item concerns what’s known as “extraterritorial control over items made using controlled items” — essentially the same idea as the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) in the U.S. export control system. This rule appeared in China for the first time in MOFCOM’s Notice No. 61, which takes effect on December 1, and corresponds to Article 49(2) of the Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items: “dual-use items manufactured abroad using PRC-origin technologies.”

The FDPR has a long history in U.S. law, generally traced back to 1959, when it was first incorporated into American export controls. The date May 15, 2020, highlighted in Zhang’s table, marks an important milestone — the point when the U.S. began applying the FDPR specifically to entities on the Entity List that were tagged with “Footnote 1.” At that time, the only companies listed under Footnote 1 were Huawei and its non-U.S. affiliates.

This marked the birth of what became known as the Entity List FDPR — a far more targeted and discriminatory form of extraterritorial control than any previous version. Since then, the U.S. Commerce Department has repeatedly expanded the FDPR, issuing a series of new, narrowly tailored rules aimed at Chinese companies and industries.

The fourth item in the expanded table — extraterritorial control over items containing controlled content — was an addition he made to Triolo’s original version. This corresponds to the de minimis rule in U.S. export control law, another long-standing feature. This concept also appeared for the first time in China’s Notice No. 61, to take effect on December 1, and aligns with Article 49(1) of the same Regulations: “dual-use items manufactured abroad that contain, incorporate, or are mixed with specific PRC-origin dual-use items.”

Annex 1 of Notice No. 61 spells this out clearly. It lists two categories of rare-earth items: if an item manufactured abroad uses materials listed in Part I to produce items listed in Part II, and if the value of those Part I materials accounts for 0.1 percent or more of the finished product’s value, then the item falls under China’s export control scope.

The U.S. de minimis rule also has deep historical roots. The foundation for extraterritorial jurisdiction in U.S. export controls can be traced back to the Export Control Act of 1949, which introduced the ideas of destination control, routing of goods, and overseas investigations. For decades afterward, the United States did not define a clear “content threshold” — meaning that even the smallest amount of U.S.-origin controlled content could trigger U.S. jurisdiction.

It wasn’t until March 1987 that Washington formally introduced a 25 percent de minimis threshold, and later lowered it to 10 percent in certain cases. Another key moment came on October 7, 2022, when the U.S. released its landmark export control rules on advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing items. In that package, the U.S. imposed a 0 percent threshold specifically for China — effectively asserting jurisdiction over any item containing even the slightest trace of U.S.-origin controlled technology.

(3) China’s Export Control Measures Are Relatively Restrained Compared with the U.S.

Compared with the United States, China’s export control system is still relatively young. It began to take shape only after the start of the reform and opening-up era and has developed gradually since then. At the legal level, China’s Export Control Law only came into effect in December 2020. In recent years, as China has responded to the tightening of U.S. export restrictions, it has learned from the American system and quickly improved its own framework. But overall, China’s approach to export controls remains measured and restrained.

At present, China’s export control list covers just over 900 items, and its extraterritorial jurisdiction applies only to certain rare earth products. By contrast, the U.S. controls more than 3,000 items, with full extraterritorial coverage across all categories.

China’s Controlled Entity List—the list of entities subject to export control restrictions—currently includes only 82 entities. Among them, 8 are from Taiwan, while the remaining 74 are U.S. entities. Under the Ministry of Commerce’s August 12 decision, prohibitive measures against 12 of the U.S. entities were lifted, and actions against another 16 U.S. entities were suspended for an additional 90 days. In other words, the number of entities actually affected by China’s restrictions remains quite limited.

China’s export control system also includes what’s known as a Watch List, somewhat similar to the U.S. Unverified List (UVL). However, so far, the Ministry of Commerce has not published the names of any entities placed on that list. This again shows that China’s export control regime is still in an early stage of development, far less expansive or mature than America’s.

The U.S., by contrast, operates a patchwork of overlapping control lists, with the Entity List being the most prominent. As of October 19, public database searches show 1,103 mainland Chinese entities listed, though the real number is estimated to be around 1,119. The discrepancy arises because the U.S. government shutdown on October 1 temporarily halted database updates by the Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration. Despite not being paid during the shutdown, officials at the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) still managed to update the Entity List on October 8, adding another 16 Chinese companies to it.

So even though both countries have now adopted the 50 percent ownership rule, the impact is vastly different in scale. Under the U.S. version, the rule potentially extends restrictions to the affiliates of more than 1,100 Chinese mainland entities, while under China’s system, it affects only a few dozen affiliates of American entities.

According to the BIS’s 2024 review of export control activities between 2018 and 2023, the U.S. government denied export license applications to China worth a total of $545 billion over those six years—an average of about $90 billion per year, equivalent to roughly 60 percent of total U.S. exports to China annually.

These figures make one thing clear: while Washington frequently accuses Beijing of “weaponizing trade” or “politicizing technology,” in practice it is the United States that has long used export controls as a primary economic weapon, while China’s measures remain far more limited in both scope and intensity.

(4) China’s Export Controls Are Far Less Discriminatory Than Those of the U.S.

One of the key differences between China’s and America’s export control systems today is that China’s measures are, in principle, non-discriminatory — they are not targeted at any specific country or region. As a result, China does not maintain destination-based groupings like the United States does.

The U.S. export control system, by contrast, divides the world into four country groups — A, B, D, and E — arranged in order of increasing restriction. Each group may contain several sub-lists depending on the specific policy objective. Group D alone contains five separate lists, and China appears on all of them. In addition, through multiple rounds of rule updates in recent years, the U.S. has explicitly identified China as its primary target for export restrictions, especially in areas such as semiconductors and advanced computing.

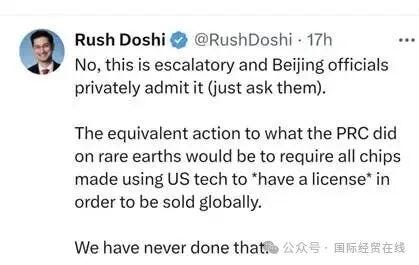

After China announced its new rare-earth export control rules on October 9, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent seized on the fact that Beijing’s export control framework is formally non-discriminatory and not directed at any particular country. He argued that this showed China was “taking on the world,” and called on America’s allies to unite against Beijing.

Meanwhile, David Sacks, Director of the China Strategy Initiative at the Council on Foreign Relations, offered a different interpretation. He contended that China’s new rare-earth export control rules were not merely a tit-for-tat response to U.S. actions but actually an escalation. According to him, if the United States were to take equivalent steps, it would mean requiring export licenses for every global sale of any chip produced using U.S. technology — something Washington has not yet done.

In other words, while Washington frames Beijing’s rare-earth measures as aggressive, China’s export control regime remains, by design and in practice, far less discriminatory and far narrower in scope than the United States’.

If we follow Rush Doshi’s logic, then what exactly would not count as an escalation? Suppose China were to adopt a U.S.-style export control system — dividing destination countries into risk-based categories, granting license exemptions for low-risk destinations that meet end-user and end-use requirements, while completely banning or presumptively denying exports to high-risk countries. Would that somehow make China’s actions more acceptable? Is that the outcome Washington really wants to see? After all, that’s precisely how the United States treats China under its own system.

The fact that China’s rare-earth export controls are not targeted at specific countries or regions does not mean that Beijing ignores the issue of risk assessment. Destination is one of the key factors considered in China’s export control licensing process. Article 8 of China’s Export Control Law explicitly provides that “the national export control authorities may assess the risk level of export destinations and adopt corresponding control measures.”

In practice, many of China’s recent export control measures have been taken in response to specific international trade and national security risks. After the Biden administration introduced multiple export restrictions against China, Beijing issued MOFCOM Notice No. 46 (December 2024) — “Announcement on Strengthening Export Controls on Certain Dual-Use Items to the United States.” That announcement stated:

Exports of dual-use items for U.S. military users or military end-uses are prohibited;

In principle, export licenses will not be granted for gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard material–related dual-use items destined for the United States; and

Exports of graphite-related dual-use items to the U.S. will be subject to stricter end-user and end-use reviews.

However, in both the April 4, 2025 and October 9, 2025 documents on rare-earth export controls, the Chinese government did not specify the United States as a target. In other words, for now, export license applications for rare-earth products intended for non-military U.S. end users are not subject to any “presumptive denial” or “enhanced end-use/end-user review” requirements. Under the current framework, U.S. civilian users not listed on China’s control lists still retain the right to apply for general licenses or simplified approvals, just like any other applicants.

Beijing’s insistence that its rare-earth controls are not aimed at specific countries and its avoidance of labeling any state as a “strategic adversary” are deliberate choices. The purpose is to keep room open for managing China–U.S. economic and trade relations through dialogue rather than confrontation.

(5) Improving Facilitation for Legitimate Trade

China has consistently advocated for trade liberalization and facilitation, and even in the sensitive area of export controls, regulators emphasize the need to minimize disruption to supply chains. That means speeding up license approvals, implementing a general licensing system for low-risk transactions, granting license exemptions in appropriate cases, and, as specified in official notices, exempting humanitarian trade from licensing requirements with a post-reporting mechanism instead.

3. Was China’s Rare-Earth Rule Long Planned?

According to an October 14 Financial Times report, a senior U.S. official complained that China had used the U.S. Department of Commerce’s late-September export control rule as a mere “excuse.” In his words, it was impossible for Beijing to have developed such a complex regulatory framework in just two weeks — meaning the policy must have been in the works for some time.

To be fair, part of what the American official said is actually true: China had indeed been preparing to establish extraterritorial jurisdiction in export controls for quite some time. What’s puzzling, though, is how this could surprise anyone in Washington. The United States has been exercising extraterritorial export control and secondary sanctions for decades. Nearly thirty years ago, laws like the Helms–Burton Act and the D’Amato Act sparked heated discussions in Chinese academic and policy circles about “long-arm jurisdiction.” Anyone searching the Chinese academic literature from that period would find countless papers analyzing U.S. extraterritorial sanctions and their impact on Chinese companies. Chinese firms have already paid a heavy price for those measures. So now that China is applying moderate extraterritorial jurisdiction of its own under export control law, how can anyone really be surprised — or claim this is unreasonable?

Back in October 2019, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China adopted a major decision on “upholding and improving the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics and advancing the modernization of China’s governance system and capacity.” Among other things, it explicitly called for accelerating the development of a legal framework for the extraterritorial application of Chinese law.

Anyone familiar with China’s social science and policy research system knows that a single line like that in a Party document usually triggers multiple national-level research projects.

The Export Control Law, which took effect in December 2020, laid the groundwork in Article 44:

“Where any organization or individual outside the People’s Republic of China violates this Law’s provisions on export control management, endangering China’s national security and interests or hindering the fulfillment of its non-proliferation obligations, such violations shall be investigated and handled according to law, and legal responsibility shall be pursued.”

This provided a legal basis for extraterritorial application of export control measures.

Then, Article 32 of the Foreign Relations Law, which came into force in July 2023, further clarified that:

“The state, on the basis of the fundamental principles of international law and the basic norms governing international relations, shall strengthen the implementation and application of laws and regulations in foreign-related fields, and may take enforcement, judicial, and other measures in accordance with law to safeguard national sovereignty, security, and development interests, and to protect the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese citizens and organizations.”

Experts noted that this was the first time China had clearly stated in law the purpose, conditions, and policy direction of applying Chinese law extraterritorially.

Building on that foundation, Article 49 of the Regulations on Export Control of Dual-Use Items, which took effect in December 2024, established the principle of moderate extraterritorial jurisdiction, authorizing the Ministry of Commerce to apply export control measures abroad when appropriate. This provided the legal basis for the Ministry’s October 2025 Notice No. 61.

Compared with the highly unpredictable trade policies of the United States, China’s policies are actually more stable and predictable. Throughout this ongoing international trade struggle, Beijing has maintained a consistent stance: “We don’t want a fight, but we’re not afraid of one. If you want to talk, our door is open; if you want to fight, we’ll stand our ground.”

On one hand, China continues to focus on domestic development, deepening reform and opening up, and accelerating the creation of a new dual-circulation development pattern linking domestic and international markets. On the other hand, it takes a bottom-line approach, preparing short-, medium-, and long-term contingency plans, firmly defending international fairness and justice, the multilateral trading system, and its own development interests.

China’s countermeasures are grounded in both domestic and international law, backed by comprehensive supporting mechanisms, and guided by a principle of measured proportionality — never premature, never excessive, always leaving room for adjustment. The principles are clear, the methods flexible.

Whenever foreign actions seriously harm China’s interests — especially when they violate treaty obligations or impose discriminatory measures against China — Beijing will respond.

Take, for example, the U.S. Section 301 investigation into China’s maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors. It began a year and a half ago, and six months ago, Washington issued its related measures, setting a 180-day transition period. Throughout this period, Chinese agencies and companies cooperated with the U.S. investigation, while the Chinese government maintained active communication with Washington, seeking every possible way to resolve the issue peacefully.

It wasn’t until October 14, on the eve of the U.S. implementation of new port fees, that China introduced its reciprocal countermeasures, imposing special port charges on U.S. shipping companies and vessels — neither jumping ahead nor lagging behind.

China acts on the principle of reciprocity, but the form of reciprocity is flexible — not necessarily “equal in scale” or “equal in amount.” The goal is not retaliation for its own sake, but to deter further harm and encourage a return to mutually beneficial cooperation.

Recently, some media outlets have reported that China and the United States have discussed expanding Chinese investment in the U.S. economy. While the authenticity of those reports remains unclear, we believe that greater two-way investment cooperation — with both sides working to allow and even promote expanded Chinese investment in America — would help stabilize and strengthen U.S. manufacturing, while also providing new opportunities for Chinese companies. It would be a win-win outcome for both economies.

Unfortunately, the main obstacle today lies within the United States itself: a widespread misunderstanding of China, a shortage of qualified China experts, and the simultaneous rise of both the “China threat” and “China collapse” narratives — trends that have made it increasingly difficult for Washington’s decision-makers to approach complex issues with a clear head.

4. Advancing U.S.–China Economic and Trade Negotiations on the Basis of Equality and Mutual Benefit

One of the most pressing challenges in U.S.–China trade talks today is that progress is often disrupted. Time and again, just after the two sides reach an agreement, new restrictive measures suddenly emerge, undermining the results of negotiation. Recently, some experts have debated whether the two sides ever reached an understanding — formal or informal — to refrain from introducing new restrictions during the negotiation period. Whether such a consensus ever existed or not, allowing new measures to keep surfacing serves no one’s interests and certainly does not help stabilize the economic relationship between the two countries.

Going forward, U.S. and Chinese economic teams should stay firmly focused on the right direction and conduct negotiations based on the consensus reached between the two heads of state, whether through phone calls or in-person meetings. Not long ago, the U.S. trade representative expressed surprise at China’s October 9 measures, while the Chinese side stated that it had already notified Washington in advance through the bilateral export control dialogue mechanism. We have reason to believe both accounts are true — which suggests that information-sharing and coordination among different U.S. government departments could use some improvement.

Although the two countries differ in political systems and decision-making mechanisms, mutual respect and direct communication between the top leaders have provided a solid foundation for managing differences and remain a key stabilizing factor in the U.S.–China economic relationship.

The two sides should also reach some form of understanding on the negotiation process itself. In international trade negotiations, there are generally three widely recognized mechanisms:

A standstill mechanism before and during talks, meaning neither side should “create new cards out of thin air” by introducing fresh barriers or restrictions;

A rollback mechanism during the negotiation process, under which both sides gradually scale back existing barriers through negotiation; and

A ratchet mechanism after agreements are reached, ensuring that neither side undermines the progress already made by imposing new restrictions.

The exact scope and implementation of these mechanisms can, of course, be further discussed and tailored to the specifics of the U.S.–China context.

Finally, both sides need to explore new areas of cooperation. As two major powers in today’s world, China and the United States both stand to gain from cooperation and both stand to lose from confrontation — and Beijing is under no illusion about this reality. From the beginning of the trade war in 2018 to today, it has become increasingly clear to many observers that decoupling or severing supply chains is neither realistic nor sustainable, and that pursuing “de-risking” solely for one’s own benefit while ignoring others’ interests is a dead end.

The only right path forward is for both countries to respect each other’s core interests, work together to address their respective challenges as well as the shared challenges facing humanity, and recognize the fundamentally mutual and beneficial nature of their economic relationship. Upholding this principle of mutual benefit through cooperation is the only viable way for the U.S.–China trade relationship to move toward stability and long-term development.

This really is the most objective analysis of the export control rules in China vs US that I have seen. China Talk (a publication on a Substack) should publish this instead of the “rubbish” written by Western scholars. 😅