China's "Hangzhou Six Young Dragons"Share the Stage; DeepSeek Researcher Voices Concerns Over AI Impact

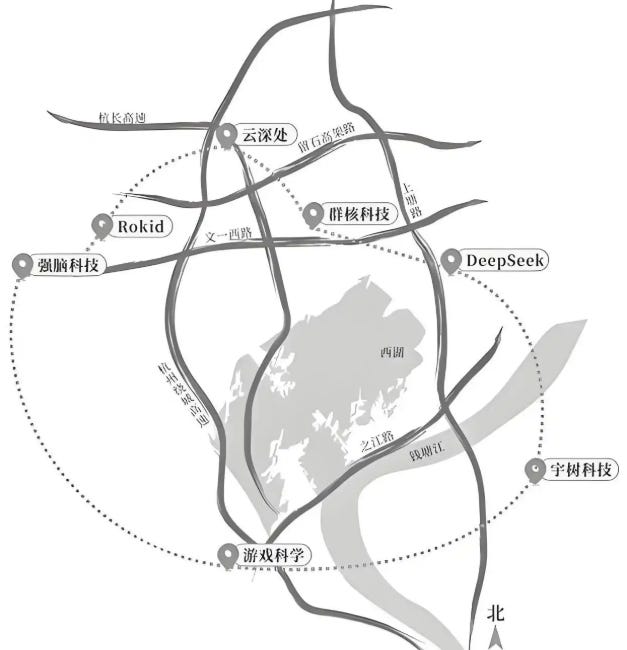

In recent years, the term “Hangzhou’s Six Young Dragons” has become the best shorthand for China’s new generation of AI powerhouses. It refers to six fast-rising tech innovators from Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province (Unitree Robotics, DeepSeek, Game Science, BrainCo, Deep Robotics, and Many Core), each a pioneer in cutting-edge fields like robotics, AI, game development, brain–computer interfaces, and spatial intelligence. The phrase started gaining traction in Chinese media and online discussions between late 2024 and early 2025.

Today, at the 2025 World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, the “Six Young Dragons” shared the stage for the first time. All founders showed up in person, except for DeepSeek’s founder Liang Wenfeng, who sent a senior researcher instead to represent him. The session was moderated by Wang Jian, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and the founder of Alibaba Cloud.

(photo South Weekly)

Unsurprisingly, DeepSeek’s representative, senior researcher Victor Chen (陈德里), became one of the focal point of the discussion, as DeepSeek rarely speak out in public before. Mr. Chen shared several remarks that drew attention.

(photo from Reuters)

From the very beginning, DeepSeek has set the realization of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) as its fundamental goal. In pursuing this vision, DeepSeek has always focused on cutting-edge, hard-core technological exploration. One of DeepSeek’s core strengths lies in its long-term orientation, staying firmly on the main track of frontier breakthroughs in intelligence, while consciously letting go of short-term, quick-gain projects.

The evolution of AI brings both opportunities and risks, and the role of technology companies should evolve accordingly. In the next three to five years, humanity and AI will likely remain in a “honeymoon period,” where people use AI to solve increasingly complex problems and create greater value—achieving a “1 + 1 > 2” effect. During this phase, technology companies should act as “evangelists,” striving to make AI technology accessible and beneficial to all.

In the five-to-ten-year horizon, AI will begin to replace certain human jobs, raising unemployment risks. At that point, technology companies should serve as “whistle-blowers,” alerting society to the labor market disruptions caused by AI applications, identifying which roles are at risk of automation, and which skills are losing value. Looking further ahead, ten to twenty years from now, AI’s substitution of human labor may become widespread, potentially reshaping or even destabilizing existing social orders. Then, technology companies must take on the role of “guardians,” ensuring human safety and helping to rebuild the future social framework.

This is not an alarmist view. The ongoing AI revolution differs fundamentally from past industrial revolutions. Historically, the tools humans invented were merely objects of human intelligence, while human wisdom remained the subject. In contrast, AI itself can become an independent subject of intelligence, potentially surpassing human intellect. The consequence is that as AI replaces human labor, it may not generate enough new jobs in return. Humans could be completely liberated from work—which may sound like a blessing, but in reality, it poses profound challenges to the existing social order.

The other five founders also offered their own perspectives on embodied AI, brain–computer interfaces, and gaming innovation:

Wang Xingxing, founder of Unitree Robotics:

Embodied AI still has a long way to go. Large language models have the internet’s massive datasets to feed on, but in robotics, both model architecture and data scale hit real bottlenecks. When different robot makers collect data, the variations in form and hardware mean the data isn’t consistent. Everything, from how we collect data and how much is needed, to filtering useful data and running reinforcement learning on real hardware, is still in the experimental stage.

I’m optimistic about humanoid robots. Compared with goals like nuclear fusion or Mars colonization, embodied intelligence seems much more attainable. In the next few years, many sci-fi ideas will start to take shape in reality, and the surprises coming next year or the year after might even top what we’ve seen this year.

Zhu Qiuguo, founder of CloudMinds:

Whether robotic hands can perform complex, uncertain, long-sequence tasks with true dexterity, that’s still an open question. The only dignity left to humankind, perhaps, lies in our two hands.

Huang Xiaohuang, co-founder of Kujiale (Coohom):

Before the generative AI boom, our company mainly made spatial design software. But after 2023, we pivoted toward serving robotics hardware firms. Robots operate in the physical world. They must perceive, reason about, and act within space, all core aspects of spatial intelligence.

These embodied-AI firms have incredibly strong in-house R&D. To become the ‘water seller’ in a gold rush like this, serving them rather than competing, is a daunting business challenge.

Han Bicheng, founder of BrainCo:

Brain–computer interfaces have huge potential in treating brain disorders like Alzheimer’s, autism, and insomnia. But the challenges are formidable, mainly in how we collect and interpret data. The brain is insanely complex, with something like 86 to 100 billion neurons, and decoding their signals is incredibly hard.

For example, our company is developing a smart bionic hand powered by brain–computer interface technology. Converting the brain’s lightning-fast thoughts into ultra-precise hand movements is a massive technical hurdle.

Feng Ji, founder of Game Science (developer of Black Myth: Wukong):

The success of Black Myth: Wukong taught us something important. We used to think Chinese users always preferred foreign brands, that ‘the moon is rounder abroad,’(外国的月亮更圆) so to speak. But the opposite might be true: whether in content or technology, when a Chinese team builds a genuinely solid product, one that reaches or even approaches global standards, domestic users often respond with enthusiasm and pride that far exceed the product’s intrinsic value.

On the flip side, if your content is mediocre or your product is shoddy, Chinese users will see right through it. They’ve got their own pair of fiery, discerning eyes.

Even though most of these companies still focus mainly on the Chinese market, some of them have already drawn attention from U.S. politicians and policy circles.

DeepSeek, in particular, has drawn intense scrutiny in the U.S. for its rise in the general AI field and its Chinese roots. Multiple U.S. media outlets and security agencies have described it as a potential threat to national security and data privacy. The U.S. Department of Commerce and several federal agencies have already banned the use of DeepSeek products on government devices, and many state governments have followed suit.

In 2025, the U.S. House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party went further, accusing DeepSeek of serving as a possible tool of “technological infiltration and influence operations” and proposing the No Adversarial AI Act, which would restrict U.S. government procurement or use of AI models developed by Chinese companies.

Think tanks such as CSIS have also warned that while DeepSeek has achieved high-performance models at very low cost, uncertainties remain around its data flows and algorithmic transparency, issues that warrant caution from the perspectives of technological competition, cybersecurity, and ideological influence.

Similarly, BrainCo has faced its own controversy in the United States. The company’s brain–computer interface products, used in educational and athletic settings, have drawn the attention of Congress and regulators. In September 2025, the House Energy and Commerce Committee sent letters to the Justice Department and Commerce Department, demanding a full investigation into whether BrainCo collected brainwave data from American students and athletes and whether it had undisclosed ties to the Chinese government or military.

U.S. media outlets reported that BrainCo’s headband devices might be transmitting neural data to Chinese research institutions or military entities, sparking concerns over biometric data leaks. Lawmakers noted that the company’s devices were being used by minors and collected highly sensitive neural information, potentially violating privacy and national-security rules.

Analysts argue that the BrainCo case highlights the ethical and security gray zones in brain–computer interface technologies and reflects Washington’s growing strategic anxiety over China’s progress in intelligent systems, bio-data collection, and human–machine integration.