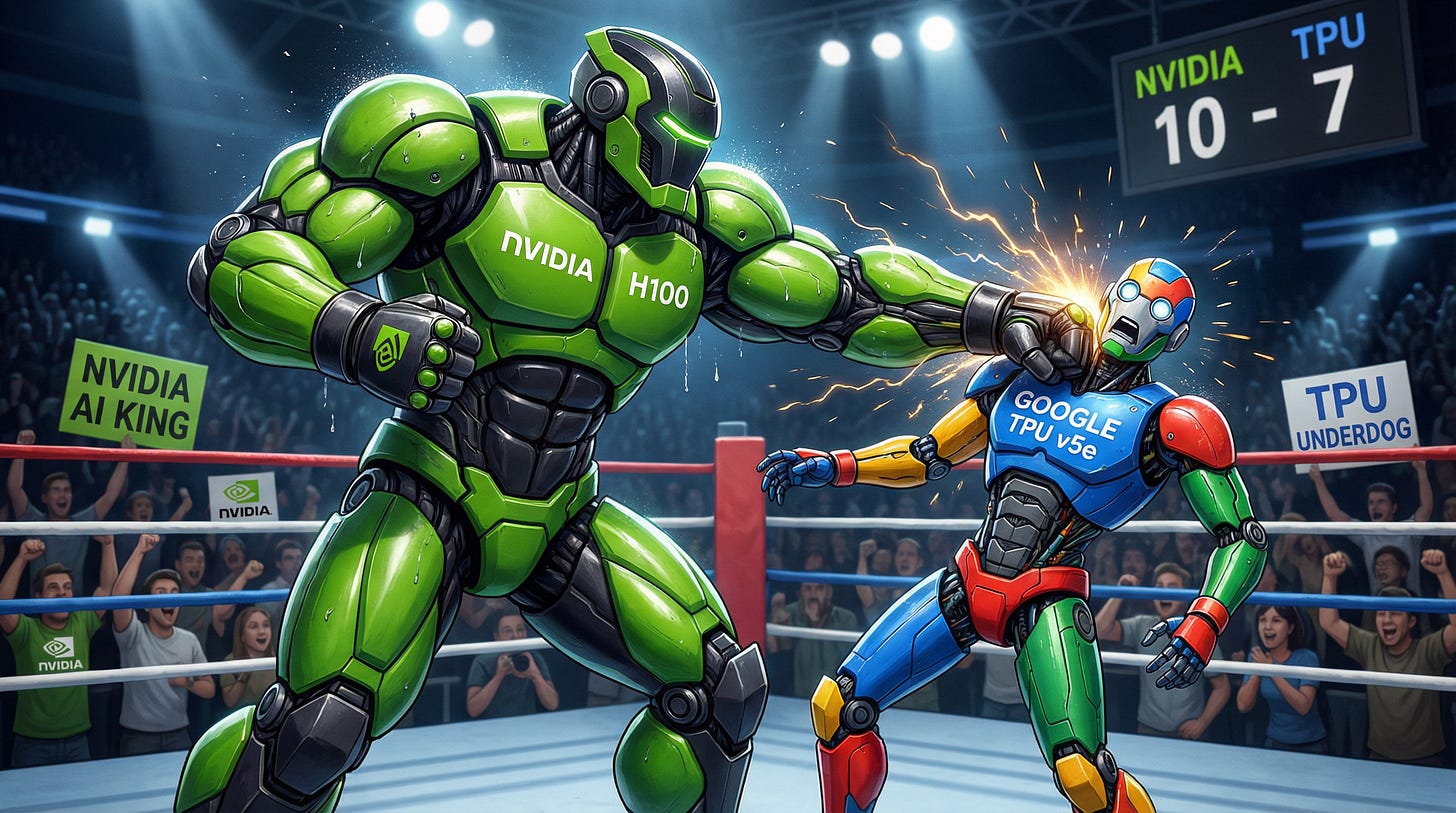

Are TPUs beating GPUs?

After Gemini and nano banana models made headlines, people started arguing again about whether GPUs or TPUs are better. It’s not a new debate; it pops up every so often, and TPUs themselves have been around for a while. But by now, it’s not just about who makes the better chip. The real competition is about system-level performance, cluster deployment, and how much it costs to run these AI “factories” over their whole life cycle.

One common misunderstanding is around cost. Yes, TPUs are generally cheaper to make; they’re custom chips (ASICs) designed with cost in mind. But you can’t just compare the TPU material cost to the retail price of the NVIDIA GPU; that’s not fair.

For Google, the real savings come from avoiding what some call the “NVIDIA tax” — licensing or tech fees tied to using their GPUs. But the right way to compare is by looking at three things: how much it costs to buy and build clusters, how much it costs to run the system, and the total cost over time. As Jensen Huang likes to point out, even if your competitor gives you chips for free, it still might not be worth it once you factor in everything else.

This becomes super clear when you look at what it takes to run a 1-gigawatt data center. Using NVIDIA’s Grace Blackwell setup, total capital costs are about $39,000, with GPUs making up 43% of that. A more basic ASIC setup, like TPU, only costs about $23,000, with no GPU costs, but building out the infrastructure makes up 69% of the total.

And when you look at running costs and performance, the differences grow: Grace Blackwell costs more per hour but delivers way more usable output. The bottom line is that cheap hardware often means worse performance. When you’re running AI at a massive scale, looking at just hardware or price isn’t enough. In most real-world situations, NVIDIA wins on overall cost-efficiency.

Jensen Huang’s “AI factory” idea explains a lot. Some argued that, since Transformer-based AI follows a fixed pattern (load model, take prompt, return answer), ASICs like TPUs could do the job more cheaply. But Jensen says what really matters is efficiency and output per watt. Energy is the main bottleneck, not chip costs. So saving money on chips but burning more power just isn’t smart. NVIDIA’s GPUs might be pricey, but they give you the best bang for your electricity buck.

That’s why “power efficiency” is NVIDIA’s secret weapon. The limit in most data centers isn’t money, it’s electricity. Jensen introduced a new way to measure value: how much you can get done with the same power. Under a 1-megawatt limit, Blackwell chips outperform older Hopper ones by 25x. So even if Amazon’s TPUs are cheaper, their weaker energy efficiency means you get fewer tokens out of your power budget.

And NVIDIA GPUs are flexible. AI needs to balance high throughput (handling lots of users) with low latency (quick replies). ASICs like TPUs tend to be good at one thing or the other, but they can’t do both well. Once they’re built, they’re locked in. NVIDIA’s secret sauce is its software — with tools like Dynamo, it can reassign GPU power based on what’s needed. Need to browse the web or write long research? Use more compute up front. Need to chat fast? Focus on speed. That flexibility means NVIDIA isn’t just selling chips, it’s selling a full operating system for AI compute.

Now, let’s talk survival. With ASICs, there’s no “good enough.” Either they hit at least 50% of NVIDIA’s performance, or they’re not worth it. Only Google’s TPUs have made the cut so far. A study showed that if your custom chip hits only 70% of NVIDIA’s performance, your returns plummet. If you’re down to 50%, it’s barely a draw. Below that, it’s a losing game. So the performance gap isn’t just tech, it’s financial life or death.

And it’s not enough to build one good chip. You need to stay on pace with NVIDIA’s upgrade cycle. From Hopper to Blackwell to Rubin and Rubin Ultra, NVIDIA keeps pushing hard. Jensen says that with 36,000+ people focused on one goal, no small team can keep up. Big tech firms aren’t just buying chips; they’re betting on a roadmap. Switching to TPU means ripping out and rebuilding data centers, cooling, everything. That’s a massive investment. Even Google’s TPUv8 was criticised for being too conservative — not using the best memory or manufacturing tech available. Meanwhile, NVIDIA and AMD are already working with 3nm and HBM4.

And there’s the supply chain. Two things are in short supply: energy and TSMC’s advanced chip packaging. NVIDIA has deep relationships with TSMC and gets preferred access. That means faster product cycles and more revenue to reinvest in R&D. Even a great TPU can’t scale without those resources. NVIDIA’s suppliers are also more willing to share risk and invest in new designs. For ASICs, where margins are thin, that’s harder.

Google also faces a unique challenge. It’s both a cloud provider and AI developer. That makes it tricky for rivals to use its chips; they’d be relying on a competitor’s infrastructure. Anthropic uses TPUs largely because Google invested heavily. Meta uses them too, but mostly because it has its own chip team. In this way, Google’s approach looks more like Intel’s, trying to be both designer and manufacturer, while NVIDIA is more like TSMC: a pure accelerator platform everyone can use.

In the end, TPUs are strong contenders, but the panic around them is overblown. Google isn’t trying to sell TPUs to the world; it’s using them to strengthen its own AI and cloud business. Google competes with OpenAI in AI, and with AWS in cloud. But its relationship with NVIDIA is more complementary. As models like Gemini grow, AI demand will only keep rising. That probably means even more GPU orders, not fewer.

This isn’t a zero-sum game. The pie is still getting bigger. The real competition and advantage will come down to how well each side balances tech performance, cost, and ecosystem support. The GPU vs TPU race is far from over.