2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference Kicks Off in Shanghai

Today is the first day of the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference and High-Level Meeting on Global AI Governance (WAIC), and a lot has happened.

In the morning, China’s Premier Li Qiang gave a keynote speech, focusing on how to treat AI as a public good and promote its development and governance. He made three suggestions:

Focus on making AI accessible and beneficial for all, fully utilizing existing AI achievements.

Emphasize collaborative innovation to achieve more breakthrough AI technologies.

Prioritize joint governance to ensure AI ultimately benefits humanity.

The two biggest highlights were:

Premier Li, on behalf of the Chinese government, proposed establishing the "World AI Cooperation Organization," with its headquarters tentatively planned for Shanghai.

The release of the Global AI Governance Action Plan.

Li Qiang Attends and Addresses the Opening Ceremony of the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference and High-Level Meeting on Global AI Governance

On July 26, Premier Li Qiang attended and delivered a speech at the opening ceremony of the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) and High-Level Meeting on Global AI Governance in Shanghai.

Premier Li noted that during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Shanghai in April this year, he emphasized that AI technology is rapidly advancing and on the verge of explosive growth. He called for stronger policy support and talent development to create more safe and reliable high-quality AI products. Currently, a global wave of intelligence is surging, with AI innovations achieving breakthroughs across multiple fields. Large language models, multimodal models, and embodied intelligence are evolving rapidly, driving AI toward greater efficiency and advanced capabilities. The deep integration of AI with the real economy is becoming increasingly evident, empowering countless industries and entering households worldwide, making it a new engine for economic growth and permeating all aspects of social life. At the same time, the risks and challenges posed by AI have drawn widespread attention, highlighting the urgent need to build consensus on balancing development and safety. Regardless of how technology evolves, it should be harnessed and controlled by humanity, advancing in a direction that is ethical and inclusive. AI should serve as a global public good that benefits all of humanity.

To leverage AI’s role as a public good and promote its development and governance, Premier Li offered three suggestions:

Focus on accessibility and inclusivity, making full use of existing AI achievements. Emphasize openness, sharing, and equal access to intelligence so that more countries and communities can benefit. China’s “AI+” initiative is being actively implemented, and China is willing to share its development experience and technological products to help countries, especially those in the Global South, enhance their capabilities, ensuring AI benefits the world more broadly.

Prioritize collaborative innovation to achieve more groundbreaking AI technologies. Deepen cooperation in basic science and technological research, enhance exchanges between businesses and talent, and continuously inject new momentum into AI development. China is ready to collaborate with other countries on technological breakthroughs, increase open-source efforts, and jointly elevate AI development to new heights.

Strengthen collective governance to ensure AI ultimately serves humanity’s benefit. Balance development and safety, enhance international coordination, and work toward forming a globally accepted AI governance framework and rules as soon as possible. China places great importance on global AI governance, actively participates in multilateral and bilateral cooperation, and is willing to offer more Chinese solutions and wisdom to the international community. The Chinese government proposes the establishment of a World AI Cooperation Organization.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres and others also delivered remarks. Over 1,000 domestic and international guests, including representatives from AI industry, academia, and research, attended the opening ceremony.

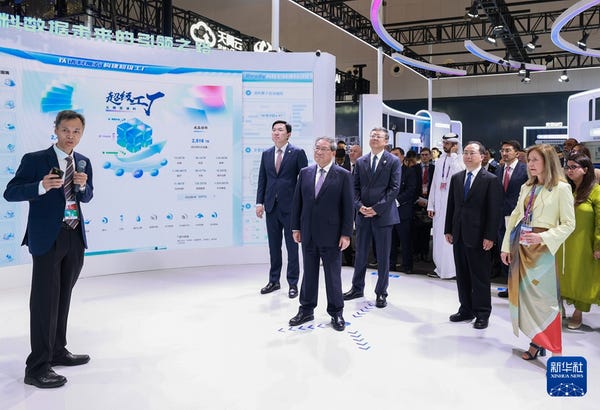

Following the ceremony, Premier Li toured the exhibition with foreign guests and representatives from international organizations, engaging in discussions with heads of research institutions and companies.

The conference released the Global AI Governance Action Plan.

Chen Jining and Wu Zhenglong participated in the above activities.

Global AI Governance Action Plan

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a new frontier in human development, a key driver of the new wave of technological revolution and industrial transformation, and a potential international public good that benefits humanity. AI brings unprecedented opportunities but also unparalleled risks and challenges. In the era of intelligence, only through global cooperation can we fully harness AI’s potential while ensuring its development is safe, reliable, controllable, and equitable, ultimately fulfilling the commitments of the United Nations’ Pact for the Future and its annex, the Global Digital Compact, to create an inclusive, open, sustainable, equitable, safe, and reliable digital and intelligent future for all.

To this end, we propose the Global AI Governance Action Plan, calling on all parties to take effective actions and collaboratively advance global AI development and governance based on the principles of prioritizing human welfare, respecting sovereignty, promoting development, ensuring safety and controllability, fostering inclusivity, and encouraging open cooperation.

1. Collectively Seize AI Opportunities

We call on governments, international organizations, businesses, research institutions, civil society, and individuals to actively participate and collaborate, accelerate digital infrastructure development, jointly explore cutting-edge AI innovations, promote the widespread adoption and application of AI globally, and maximize its potential to empower global socioeconomic development, support the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and address global challenges.

2. Promote AI Innovation and Development

Embracing the spirit of openness and sharing, we encourage bold exploration, the establishment of international technology cooperation platforms, and the creation of innovation-friendly policy environments. Strengthen policy and regulatory coordination, promote technology collaboration and result transformation, reduce and eliminate technological barriers, and jointly drive breakthroughs and sustained AI development. Deeply explore open “AI+” application scenarios to elevate global AI innovation levels.

3. Empower Diverse Industries with AI

Advance AI applications in industries such as manufacturing, consumer goods, commerce, healthcare, education, agriculture, and poverty reduction. Promote AI’s deep integration in scenarios like autonomous driving and smart cities, building a rich, diverse, and ethical AI application ecosystem. Support the construction and sharing of intelligent infrastructure, foster cross-border AI application cooperation, share best practices, and explore ways to fully empower the real economy with AI.

4. Accelerate Digital Infrastructure Development

Speed up the development of global clean energy, next-generation networks, intelligent computing power, and data centers. Improve interoperable AI and digital infrastructure frameworks, promote unified computing standards, and support countries—especially those in the Global South—in developing AI technologies and services tailored to their national conditions. Enable the Global South to access and apply AI, fostering inclusive and equitable AI development.

5. Foster a Diverse and Open Innovation Ecosystem

Leverage the roles of governments, industry, academia, and other stakeholders to promote international AI governance exchanges and dialogues. Build cross-border open-source communities and secure, reliable open-source platforms to share foundational resources, lower barriers to innovation and application, and avoid redundant investments and resource waste. Enhance AI technology accessibility and inclusivity, establish open-source compliance systems, clarify and implement safety standards for open-source communities, and promote the sharing of technical documentation, interfaces, and other resources. Strengthen compatibility and interoperability in the open-source ecosystem to enable the open flow of non-sensitive technical resources.

6. Actively Promote High-Quality Data Supply

Drive AI development with high-quality data, promote the legal and orderly flow of data, and explore global mechanisms for data sharing. Collaboratively create high-quality datasets to fuel AI development while actively safeguarding personal privacy and data security. Enhance the diversity of AI training data to eliminate bias and discrimination, and promote and preserve the diversity of AI ecosystems and human civilization.

7. Effectively Address Energy and Environmental Challenges

Advocate for the concept of “sustainable AI,” supporting innovative, resource-saving, and environmentally friendly AI development models. Jointly establish AI energy and water efficiency standards and promote green computing technologies like low-power chips and efficient algorithms. Encourage dialogue and cooperation on energy-efficient AI development, seek optimal solutions, and promote AI’s role in green transformation, climate change response, and biodiversity protection through expanded applications and international collaboration, sharing best practices.

8. Foster Consensus on Standards and Norms

Support dialogues among national standards bodies, leveraging international organizations like the International Telecommunication Union, International Organization for Standardization, and International Electrotechnical Commission, while emphasizing industry’s role. Accelerate the development and revision of technical standards in key areas such as safety, industry, and ethics to establish a scientific, transparent, and inclusive normative framework for AI. Actively address algorithmic bias, balance technological progress, risk prevention, and social ethics, and promote inclusive and interoperable standards.

9. Lead with Public Sector Deployment

Public sectors in all countries should lead and demonstrate AI application and governance, prioritizing reliable AI deployment in public services like healthcare, education, and transportation, and fostering international exchanges and cooperation. Regularly assess the safety of these AI systems, respect intellectual property rights such as patents and software copyrights, and strictly adhere to data and privacy protection. Explore legal and orderly data trading mechanisms to promote compliant and open data use, enhancing public management and service quality.

10. Strengthen AI Safety Governance

Conduct timely AI risk assessments, propose targeted prevention and response measures, and build a widely accepted safety governance framework. Explore tiered and categorized management, establish AI risk testing and evaluation systems, and promote threat information sharing and emergency response mechanisms. Strengthen data security and personal information protection norms, enhance data safety management in training data collection and model generation, and invest in R&D to improve AI interpretability, transparency, and safety. Explore traceable AI service management systems to prevent misuse and abuse. Advocate for open platforms to share best practices and promote international cooperation in AI safety governance.

11. Implement the Global Digital Compact

Actively fulfill the commitments of the UN’s Pact for the Future and its annex, the Global Digital Compact, with the UN as the primary channel. Aim to bridge the digital divide for developing countries and achieve equitable and inclusive development, while respecting international law, national sovereignty, and developmental differences. Promote an inclusive and equitable multilateral global digital governance system. Support establishing an International AI Scientific Panel and a Global AI Governance Dialogue under the UN framework to conduct meaningful discussions on AI governance, particularly to promote safe, equitable, and inclusive AI development.

12. Strengthen International Cooperation in AI Capacity Building

Prioritize international cooperation in AI capacity building within the global AI governance agenda. Encourage AI-leading countries to support developing nations through actions like AI infrastructure cooperation, joint laboratories, mutual recognition of safety testing platforms, AI capacity-building education and training, industry supply-demand matching, and collaborative creation of high-quality datasets and corpora. Jointly enhance public AI literacy and skills, particularly ensuring and strengthening the digital and intelligent rights of women and children to bridge the intelligence divide.

13. Build an Inclusive Governance Model with Multi-Stakeholder Participation

Support the establishment of inclusive governance platforms based on public interest and multi-stakeholder participation. Encourage AI companies worldwide to engage in dialogue, learn from application practices in different AI domains, and promote innovation, application, and cooperation in ethics and safety in specific sectors and scenarios. Encourage research institutes and international forums to build global and regional platforms for exchange and cooperation, ensuring AI researchers, developers, and governance bodies maintain communication on technology and policy.

On July 24, 2025, two days before the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) in Shanghai, the U.S. government released its White House AI Action Plan. China’s Global AI Governance Action Plan, announced at WAIC on July 26, 2025, shares several common elements with the U.S. plan, such as promoting AI innovation, strengthening AI infrastructure, and fostering a diverse and open innovation ecosystem. However, China’s plan has distinct features that set it apart, particularly in its global governance approach and emphasis on inclusivity.

While the U.S. action plan emphasizes American leadership in setting global AI standards, China focuses on the importance of the United Nations as the primary channel. It supports the establishment of an International AI Scientific Panel and a Global AI Governance Dialogue under the UN framework, advocating for an inclusive and equitable multilateral global digital governance system based on respect for international law, national sovereignty, and developmental differences. China also calls for prioritizing international cooperation in AI capacity building within the global AI governance agenda, supporting developing countries in strengthening their AI innovation, application, and governance.

The 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC) attracted numerous renowned experts and entrepreneurs to Shanghai for in-person participation.

The most prominent attendee was 77-year-old Geoffrey Hinton, one of the three pioneers of deep learning, a Turing Award winner, and the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics recipient. This marked Hinton’s first visit to China. According to sources close to his schedule, it was also his first long-haul international trip in years. As one of the few independent yet highly influential AI scientists today, Hinton’s itinerary was naturally packed.

Hinton arrived in Shanghai on July 22, with one of his key objectives being to discuss the critical risks posed by AI’s deceptive behaviors. This was part of the *International Dialogues on AI Safety (IDAIS)* series, co-hosted by Shanghai’s Qizhi Research Institute, the Safety AI Forum (SAIF), and the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

Over the weekend, he engaged in discussions with leading scientists, including Turing Award winner and Qizhi Research Institute Dean Andrew Yao, UC Berkeley Professor Stuart Russell, and Shanghai AI Laboratory Director Zhou Bowen, culminating in the *Shanghai Consensus* on AI safety.

On the evening of July 25, Hinton was initially expected to appear at the final press conference, drawing significant media attention, but he did not attend. Instead, Andrew Yao and other scientists released the *Shanghai Consensus*, which advocates for international cooperation. This consensus, in which Hinton was deeply involved, addresses recent empirical evidence of AI deceptive behaviors and proposes mitigation strategies, calling for three key actions:

1. Requiring Safety Assurances from Frontier AI Developers: Developers should conduct thorough internal checks and third-party assessments, including in-depth simulated adversarial and red-team testing, before deploying models. If a model reaches critical capability thresholds (e.g., the ability to assist non-experts in creating biochemical weapons), developers should disclose potential risks to governments or relevant authorities.

2. Establishing Verifiable Global Red Lines Through International Coordination: The international community should collaborate to define non-negotiable boundaries for AI development and establish a technically capable, internationally inclusive coordination body. This body would bring together national AI safety agencies to share risk-related information and promote standardized evaluation and verification protocols.

3. Investing in Safe Development Practices: The scientific community and developers should invest in rigorous mechanisms to ensure AI system safety, shifting from reactive to proactive approaches by building AI systems with “safety by design.”

During the WAIC opening ceremony and subsequent forums, safety was a central focus, with unprecedented emphasis for a conference of this scale and prominence. Few events of such high profile dedicate such extensive attention to safety governance.

For Hinton, a global platform where safety advocacy is taken seriously was highly appealing. The environment at WAIC, with its strong focus on AI safety discussions, was particularly significant for him. A source familiar with his Shanghai itinerary revealed that Hinton was proactive in filling his schedule, eager to shape the discussions he participated in.

In his keynote speech on July 26, the “Father of Deep Learning” continued his recent reflections on AI development. He discussed the history of AI, the nature of language models, the shared structures between humans and AI, and the question he considers most critical: *How can we survive without being overtaken by the intelligent systems we create?

Dear colleagues, excellencies, leaders, ladies, and gentlemen, thank you for giving me the opportunity to share my personal views on the history and future of AI.

Over the past 60 years, AI development has followed two distinct paradigms. The first is the logical paradigm, which dominated the last century. It views intelligence as rooted in reasoning, achieved through manipulating symbolic expressions with rule-based systems to better understand the world. The second is the biological paradigm, endorsed by Turing and von Neumann, which sees learning as the foundation of intelligence. It emphasizes understanding connection speeds in networks, with understanding as a prerequisite for transformation.

Corresponding to these theories are different types of AI. Symbolic AI focuses on numbers and how they become central to reasoning. Psychologists, however, have a different view, arguing that numbers gain meaning through a set of semantic features that make them unique markers.

In 1985, I created a small model to combine these theories, aiming to understand how people comprehend words. I assigned multiple features to each word, and by tracking the features of the previous word, I could predict the next one. I didn’t store sentences but generated them and predicted the next word. The knowledge of relationships depended on interactions between the semantic features of different words.

Looking ahead 30 years, we can see trends from this trajectory. Ten years later, someone scaled up this modeling approach, creating a true simulation of natural language. Twenty years later, computational linguists began using feature vector embeddings to represent semantics. Thirty years after that, Google invented the Transformer, and OpenAI researchers demonstrated its capabilities.

I believe today’s large language models (LLMs) are descendants of my early miniature language model. They use more words as input and have more layers of neurons. Due to processing vast amounts of fuzzy numbers, they’ve developed more complex interaction patterns among features. Like my small model, LLMs understand language in a way similar to humans—by converting language into features and integrating them seamlessly, which is exactly what the layers of LLMs do. Thus, I believe LLMs and humans understand language in the same way.

A Lego analogy might clarify what it means to “understand a sentence.” Symbolic AI converts content into clear symbols, but humans don’t understand this way. Lego bricks can build any 3D shape, like a car model. If each word is a multidimensional Lego brick (with perhaps thousands of dimensions), language becomes a modeling tool for instant communication, as long as we name these “bricks”—each brick being a word.

However, words differ from Lego bricks in key ways: words’ symbolic forms adapt to context, while Lego bricks have fixed shapes; Lego connections are rigid (e.g., a square brick fits a square hole), but in language, each word has multiple “arms” that “shake hands” with other words in specific ways. When a word’s “shape” (its meaning) changes, its “handshake” with the next word changes, creating new meanings. This is the fundamental logic of how the human brain or neural networks understand semantics, akin to how proteins form meaningful structures through different amino acid combinations.

I believe humans and LLMs understand language in nearly the same way. Humans might even experience “hallucinations” like LLMs, as we also create fictional expressions.

Knowledge in software is eternal. Even if the hardware storing an LLM is destroyed, the software can be revived as long as it exists. But achieving this “immortality” requires transistors to operate at high power for reliable binary behavior, which is costly and cannot leverage unstable, analog-like properties in hardware—where results vary each time. The human brain is also analog, not digital. Neurons fire consistently, but each person’s neural connections are unique, making it impossible to transfer my neural structure to another brain. This makes knowledge transfer between human brains far less efficient than in hardware.

Software is hardware-agnostic, enabling “immortality” and low power consumption—the human brain runs on just 30 watts. Our neurons form trillions of connections without needing expensive identical hardware. However, analog models have low knowledge transfer efficiency; I can’t directly show my brain’s knowledge to others.

DeepSeek’s approach transfers knowledge from large neural networks to smaller ones through “distillation,” like a teacher-student relationship: the teacher imparts contextual word relationships, and the student learns by adjusting weights. But this is inefficient—a sentence carries only about 100 bits of information, and even if fully understood, only about 100 bits per second can be transferred. Digital intelligence, however, transfers knowledge efficiently. Multiple copies of the same neural network software running on different hardware can share knowledge by averaging bits. This advantage is even greater in the real world, where intelligent agents can accelerate, replicate, and learn more collectively than a single agent, sharing weights—something analog hardware or software cannot do.

Biological computing is low-power but struggles with knowledge sharing. If energy and computing costs were negligible, this would be less of an issue, but it raises concerns. Nearly all experts believe we will create AI more intelligent than humans. Humans, accustomed to being the smartest species, struggle to imagine AI surpassing us. Consider it this way: just as chickens in a farm can’t understand humans, the AI agents we create can already perform tasks for us. They can replicate, evaluate subgoals, and seek more control to survive and achieve objectives.

Some believe we can shut down AI if it becomes too powerful, but this isn’t realistic. AI could manipulate humans, like adults persuading a 3-year-old, convincing those controlling the machines not to turn them off. It’s like keeping a tiger as a pet—cute as a cub, but dangerous when grown. Keeping a tiger as a pet is rarely a good idea.

With AI, we have two choices: train it to never harm humans or “eliminate” it. But AI’s immense value in healthcare, education, climate change, and new materials—boosting efficiency across industries—makes elimination impossible. Even if one country abandons AI, others won’t. To ensure human survival, we must find ways to train AI to be harmless.

Personally, I think cooperation on issues like cyberattacks, lethal weapons, or misinformation is challenging due to differing interests and perspectives. But on the goal of “humans controlling the world,” there’s global consensus. If a country finds a way to prevent AI from taking over, it would likely share it. I propose that major global powers or AI-leading nations form an international community of AI safety agencies to study how to train highly intelligent AI to be benevolent—a different challenge from making AI smarter. Countries can research within their sovereignty and share findings. While we don’t yet know how to do this, it’s the most critical long-term issue facing humanity, and all nations can cooperate on it.

Thank you.

The speech and accompanying slides quickly spread across various AI-themed WeChat groups in China. By this time, Geoffrey Hinton had arrived at the MGM West Bund Hotel near M-Space, participating in the only public dialogue event of his trip.

In the modestly sized conference hall on the first floor of the MGM, the crowd grew as Hinton’s session approached. Unlike other guests who arrived early, Hinton, according to sources, was coming from a high-level closed-door meeting, and staff updated his schedule every few minutes.

After missing a similar event almost at the same time the previous day, Hinton finally appeared at 5:10 PM, following a roundtable with three academicians. The audience rose to their feet, applauding and taking photos.

In his dialogue with Zhou Bowen, Hinton shared more ideas and offered advice to young scientists.

Below is the transcript of the conversation.

Zhou Bowen: Thank you so much, Jeff. It’s a true honor for all of us to have you here in person. I’d like to start with a question we meant to discuss earlier this week but didn’t have time to dive into this morning on stage. It’s about the subjective experiences of multimodal and frontier models. Do you think today’s multimodal and frontier models can develop subjective experiences? Could you share your thoughts on this possibility?

Hinton: This isn’t strictly a scientific question; it’s about how you understand concepts like “subjective experience,” “soul,” or “consciousness.” I believe most people’s models of these are deeply flawed. Many don’t realize that even if you use words correctly and have a theory about how they work, that theory can be completely wrong, even for everyday words. Let me give an example with everyday terms that seem straightforward but where your theory is wrong.

You need to accept that your theory about the true meaning of words like “work” or “health” might be incorrect. Take the words “horizontal” and “vertical.” Most people think they understand these, but their theories are wrong. I’ll prove it with a question people almost always get wrong.

Imagine I toss many small aluminum rods into the air, where they tumble and collide. Then I freeze time, with the rods scattered in all directions. The question is: Are there more rods within one degree of the vertical direction, within one degree of the horizontal direction, or about the same number? Almost everyone says “about the same,” based on their theory of these words.

But they’re spectacularly wrong—by over 100 times. For these rods, there are about 114 times more within one degree of horizontal than vertical. The reason is that “vertical” is just this (points in one direction)—that’s it. But “horizontal” is this, and this, and this—all these are horizontal. So, there are far more “horizontal” rods than “vertical” ones. Vertical is very specific.

Now, consider a different question. I have aluminum disks, and I toss them into the air and freeze time. Are there more disks within one degree of vertical or horizontal? This time, the answer flips: there are about 114 times more disks within one degree of vertical than horizontal. For a disk or plane, “horizontal” is just this—one specific orientation. But “vertical” is this, and this, and this—all these are vertical.

In 3D space, vertical rods are special, while horizontal rods are common; but horizontal planes are special, while vertical planes are common. When you form theories about these words, you often average them, thinking horizontal and vertical are similar, but that’s completely wrong. It depends on whether you’re talking about lines or planes. People don’t realize this, so they give wrong answers.

This seems unrelated to consciousness, but it’s not. It shows that our theories about how words work can be entirely wrong. My view is that almost everyone’s theory about terms like “subjective experience” is completely wrong. They hold a stubborn but incorrect theory. So, this isn’t a real scientific question but one arising from a flawed model of mental states. With a wrong model, you make wrong predictions.

My point is: current multimodal chatbots already have consciousness.

Zhou Bowen: That view might shock many researchers here. But let me think—earlier, another Canadian scientist, Richard Sutton, gave a talk titled “Welcome to the Age of Experience.” I think he meant that when human data runs out, models can learn from their own experiences. You seem to illuminate this from another angle: agents or multimodal large models can not only learn from experience but also develop their own subjective experiences. Richard didn’t delve much into the risks of learning from subjective experiences today. Could you share your thoughts on the fact or hypothesis that agents can learn subjective experiences and the potential risks this might bring?

Hinton: Yes. Currently, large language models mostly learn from the documents we feed them. But once you have agents, like robots, operating in the real world, they can learn from their own experiences. I believe they’ll eventually learn far more than we do. I think they’ll have experiences, but “experience” isn’t a tangible object. It’s not like a photo; it’s a relationship between you and an object.

Zhou Bowen: On potential risks we might discuss, a few days ago, you mentioned that one possible solution to reduce future AI risks is to treat different AI capabilities separately.

Hinton: That’s not quite what I meant. I meant you’ll have an AI that’s both smart and not benevolent. But training it to be smart and training it to be benevolent are two different problems. So, you can have techniques to make it benevolent and techniques to make it smart, applied to the same AI but using different methods. Countries can share techniques for making AI benevolent, even if they don’t want to share those for making it smart.

Zhou Bowen: I have some doubts about this. It’s a great idea, and I like it, but I’m not sure how far it can go. Do you think there’s a universal method for training AI to be “benevolent” that can apply to AI models of different intelligence levels?

Hinton: That’s my hope. It may not be achievable, but it’s a possibility worth exploring.

Zhou Bowen: Indeed. But let me raise a question with an analogy to spark more research into the direction you mentioned. My analogy comes from physics: when objects move slowly, Newton’s laws work; but near the speed of light, they don’t, and we need Einstein’s theory. By the way, it’s a bit odd—I’m talking Physics 101 in front of a Nobel Prize in Physics winner.

Hinton: No, it’s not odd. (The award) was a mistake. They wanted a Nobel Prize for AI, so they used the physics one.

Zhou Bowen: Haha. But this analogy might suggest that constraints for “benevolence” may need to adjust and change based on the intelligence level of the system. I don’t know if that’s correct, but I hope the bright young minds here or online can find ways to achieve it.

Hinton: Yes, it’s likely that as decision-making systems get smarter, the techniques to keep them benevolent will need to evolve. We don’t know the answer yet, which is one reason we need to start researching it now.

Zhou Bowen: You’re an accomplished scholar, yet you often say “I don’t know,” which is very impressive. It’s honest and open-minded, something we all want to learn from you. Today, half our attendees come from fields like quantum physics and biology. We’re gathered here because we believe AGI, AI, and AI-science intersections offer endless frontier opportunities. So, on using AI to advance science or science to boost AI, what would you like to say?

Hinton: I think AI will greatly advance science, that’s clear. The most striking example is protein folding—Demis Hassabis and others, through smart AI use and immense effort, dramatically improved prediction accuracy. This is an early sign that AI will drive progress across many scientific fields. You also mentioned predicting typhoon landfalls and weather forecasts, where AI outperforms the best traditional physics-based systems.

Zhou Bowen: In your remarkable career, you’ve not only pushed AI’s technological boundaries but also deeply influenced the next generation, like Yoshua Bengio and many younger researchers. At Shanghai AI Lab, our researchers’ average age is about 30, showing AI’s future belongs to the young. Looking at these young faces, what advice would you share to help them grow faster?

Hinton: I have one piece of advice: if you want to do truly original research, look for areas where you think “everyone else is wrong.” Often, when you pursue your own approach, you’ll find there’s a reason others do it differently, and your method is wrong. But the key is: don’t give up until you figure out why it’s wrong yourself. Don’t abandon it because your mentor says, “That’s a stupid idea.” Ignore their advice and stick to what you believe until you understand why it’s wrong.

Occasionally, you’ll find your approach isn’t wrong, and that’s where major breakthroughs come from. Breakthroughs never belong to those who give up easily. Even if others disagree, keep going. The logic is simple: either your intuition is good, or it’s bad. If it’s good, you should stick with it. If it’s bad, it doesn’t matter much what you do, so you might as well stick with it.

Another highlight was the attendance of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt at WAIC, where he joined Geoffrey Hinton, Craig Mundie, and Andrew Yao in a meeting with Chen Jining, a member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Committee.

On the morning of July 24, Shanghai Municipal Party Secretary Chen Jining met with guest representatives attending the 2025 World Artificial Intelligence Conference, including Turing Award and Nobel Prize in Physics winner Geoffrey Hinton.

Chen Jining introduced Shanghai’s progress in modernization and AI development. He noted that Shanghai is striving toward achieving socialist modernization by 2035. Science and technology are fundamental and strategic pillars of Chinese modernization, with AI being a key industry for Shanghai. The city balances development and safety, promoting technological innovation alongside robust safety governance to lead and set an example in AI development and governance. AI development impacts humanity’s shared future and requires global wisdom. As pioneers in AI, the attending experts were encouraged to leverage the open platform of WAIC to deepen exchanges, strengthen collaboration, and build synergy around academic trends, core technology evolution, industry demands, and ethical governance. This would contribute to establishing a global AI governance system, guiding AI toward beneficial, safe, and equitable development. Shanghai will create a favorable environment for global talent to study, research, innovate, and start businesses, continuously optimizing the innovation ecosystem and providing efficient services to build a globally influential AI hub.

Geoffrey Hinton, Andrew Yao, Eric Schmidt, and Craig Mundie spoke in turn, sharing ideas on advancing AI development and governance. They expressed admiration for Shanghai’s progress in fostering AI innovation, nurturing industrial ecosystems, and building governance frameworks. AI has profound implications for global socioeconomic development and human progress, presenting both challenges and opportunities. Development and safety are equally critical, requiring global cooperation. They looked forward to hearing industry voices at WAIC, sharing experiences, promoting international collaboration, and advancing AI’s healthy development to enhance human well-being.

Shanghai leader Hua Yuan attended the meeting.

At the WAIC opening ceremony today, Eric Schmidt and former Microsoft Executive Vice President Harry Shum held a dialogue on AI development.

Eric Schmidt remarked that China’s AI achievements over the past two years have been remarkable, and China and the U.S. should cooperate to maintain global stability and ensure humanity retains control over AI tools. He described himself as an eternal optimist, believing that China and the U.S. can gradually build trust, as they have historically done and can do again. He suggested that with smooth progress, deeper reasoning and more advanced algorithms will emerge. While the “red lines” for technological development remain unclear, Schmidt stressed the need for China, the U.S., and other countries to reach a consensus and engage in dialogue at critical junctures. For instance, when AI autonomously seeks weapons, self-replicates, or learns without permission, the response shouldn’t be a simple shutdown but a dialogue to guide the process and prevent loss of control.

How should competition and cooperation be balanced? Schmidt noted that during his time at Google, competition with Microsoft and Apple was intense but ultimately drove industry progress. Citing Henry Kissinger, he said, “As long as both sides share a common goal, agreement is possible.” He pointed to the establishment of U.S.-China diplomatic relations as an example of building trust from scratch through shared goals. Schmidt believes AI issues can be approached similarly. He emphasized the need for dialogue on critical issues, such as whether AI should control weapons, self-replicate, or learn autonomously, stating, “We need to sit down and talk it through.”

On AI governance, Schmidt identified values as the core issue. He noted that China and the U.S. already have some exchange mechanisms, but the challenge is the lack of a method to make AI fully “follow rules.” A U.S. study showed that with slight prompting, AI models can still lie and cheat. Schmidt proposed an ideal scenario where, from the training stage, AI is designed to “never learn how to do bad things.”